With Our Mouths Open: An Interview with Sarah Gambito on Food and Lyrical Sweetness

In this interview, conducted by Emily Ellison, poet Sarah Gambito discusses her approach in crafting her latest poetry collection, Loves You—a blend of verse and various recipes arranged according to the five categories of taste. She asserts poetry and cooking share many similar properties and purposes, and she hopes the collection, in the style of a recipe book, may evoke the sentiment that “this is a poetry that can be usable, that can nourish, that can be with me in the world.” Food often harkens back to a place or a person; Gambito asks us to be thoughtful about our relationships with others in the process of cooking and sharing, and perhaps learn how, through generosity, we can make those bonds a bit sweeter.

Sarah Gambito is the author of Delivered, Matadora, and Loves You. Her honors include the Barnes & Noble Writers for Writers Award from Poets and Writers and the Wai Look Award for Outstanding Service to the Arts from the Asian American Arts Alliance. She is Associate Professor of English and Director of Creative Writing at Fordham University and co-founder of Kundiman, an organization serving Asian American writers.

Emily Ellison: Your most recent poetry collection, Loves You, deliciously incorporates recipes and sprinklings of food throughout. For you, how are food and poetry related? Do you find that the preparation of food is a similar practice to the composition of poetry?

Sarah Gambito: Yeah! I feel like I’m at a point in my life now where I want to take how I approach cooking and apply that to writing. I think sometimes we can just get in our heads as writers—“Oh, how do I make this sort of perfected thing?” Whereas the audience for something you cook is someone you love, and they’re hungry, and you’ve got to make it happen. One doesn’t necessarily overthink these acts of offering in the same way that one does for poetry. I was really enjoying the wisdom of how we approach the making of food and how that can be applied to writing poetry. Absolutely.

Ellison: Yes, especially since I’d say we consume poetry in the same way we consume food: for nourishment.

The epigraph of your collection, a quote from Lin Yutang, reads: “What is patriotism but the love of the food one ate as a child?” In some poems, certain regional foods are forbidden to be prepared; I’m curious about how that might affect an individual. Could you speak on how the sentiment of this epigraph might be complicated for an immigrant who is pressured to find new patriotism?

Gambito: Right, right [deep sigh]. I’ll say that what I was doing with that epigraph is that there’s something about what you’re drawn to—what you crave, how you’re nourished, how that’s made manifest in food, that says a lot about who you are and how you want to be in the world and where your allegiances lie.

Ellison: Absolutely. In the poem “One Night Only,” you write “Everyone is my friend. / Would you like some of my sandwich? / I really mean you can come forward / with your mouth open.” I found this to be such a sweet and stirring sentiment. What would it mean if we could approach each other this way, mouths open?

Gambito: With the idea of a default towards generosity. That poem came out of a joke that my family would like to tell each other. Filipinos, and Filipino-Americans, have a relationship to food in that if you invite someone [by asking them] “Do you want some?” it’s not a gesture. If you offer a Filipino, “You want to taste this?” the Filipino’s going to bite your sandwich! [both laugh] I feel like the more American trope is, “Oh, would you want some?” And you say “Oh, no thank you.” You’re not really asking because you’re asking. Whereas somebody’s going to take you up on that if they’re Filipino—and that I love! I wouldn’t ask you unless I really meant it, you know?

Ellison: Of course! So, the collection’s poems are arranged into the five flavors: umami, sour, salt, bitter, sweet. I’m interested in your process of arranging poems according to these palates.

Gambito: I will say that I wanted to make a book that was like a recipe book, so [Loves You] sort of harkens to that idea of sections. It’s the convention. I read a lot of recipe books, also. I wanted to organize alongside taste, and I arranged it ending with sweet, for instance, because I wanted to draw in some kind of narrative arc. So, where you land on dessert at the end, I wanted to end on a kind of lyrical sweetness.

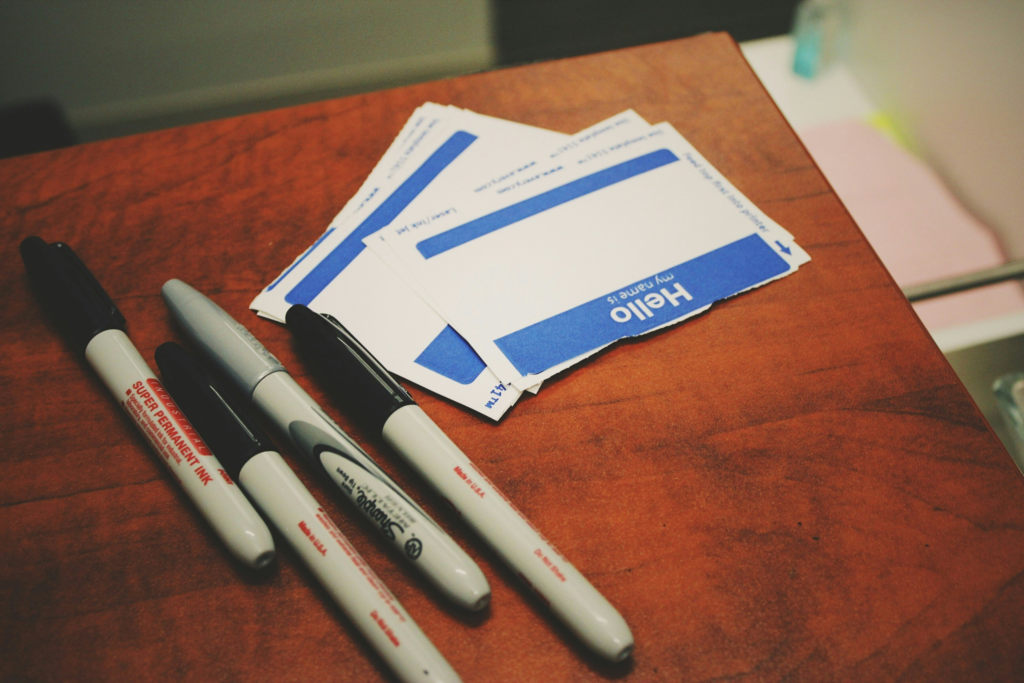

When you pick up a recipe book, often they’re all so different—it’s like, “How do you use this book?” That’s the first piece, because it’s mimicking this idea that “Oh, perhaps this is a poetry that can be usable, that can nourish, that can be with me in the world,” as opposed to just words on the page.

Ellison: How did you come to know the flavors of your poems? Did you write each poem with an intended flavor?

Gambito: Oh, no, no, no. I had a big morass of poems, a big, big morass, and I was like, “Okay, what do I do? And how does it taste to me, this poem? And then, on a pure, intuitive level, where does it belong? Is it sweet, is it salty, is it umami?” And obviously, many poems are many of those things. But just going with pure gut reaction, reading the poem aloud, thinking about what it does and how it resolves or doesn’t resolve—I sort of just relied on my intuition.

I really liked the idea of the listing of ingredients, the command of what to do with them as a kind of interactive poem. At the end of it, hopefully they’re words that will feed you—and if you actually make the recipe, a meal that can also feed you.

Ellison: And I love that you use the word “gut” because, again, that’s a link between poetry and food; what we taste resonates deeply, both with words and cuisine.

This may seem a little bit chicken and egg, but do you sense that your love for writing poetry came first, or your love for cooking? Which most informs the other?

Gambito: Definitely I would say writing poetry first. And then cooking, here and there, but I don’t think I really had a sense of an intuition about it until maybe 2012, when I had to cook so much, just to make food for my family. I like food as a project because you’re just exploring.

And that’s one thing, but when day in and day out you have to cook, then you learn in different ways. I never thought I would be one of those people who would measure with my fingers—and that’s taken a long time to do, but now I feel like I have some confidence with doing something like that.

Ellison: And it seems that that transformation occurs in the same way with practiced writing, too, when the need is beyond us—that movement away from the personal towards a collective audience, from something more along the lines of a hobby to something that’s daily and necessary and sustaining.

Gambito: Yes! For instance, take cooking and meditation. After one meditates, one doesn’t think, “Oh, that was a terrible meditation.” You know? One doesn’t excoriate or judge an act of meditation—at least I don’t—at that level. And the same with cooking—some dishes may not turn out as good, but you’re still like, “Oh! Okay.” Whereas with a poem, one’s ego can really interfere and stop you from trying again. And maybe the idea is that, in most instances, many of us cannot stop—you can’t just say, “I’m opting out, I’m not going to cook again.”

Ellison: We’d be hungry forever with that attitude!

Gambito: Right! And we can look at poetry as a meditation also, as just something for sustenance that you do without the kind of ego-driven back-and-forth that can occur.

Ellison: Digging a little deeper into your relationship with food: do you have a specific ingredient that returns to you, one that you are eager to use in most of your recipes or compositions?

Gambito: Just one?! Hmmm…. I’m thinking about that. [long pause]

I think you have to have really good salt. All salt is not created alike. I love Kosher salt, sea salt, and Maldon salt. I use all three kinds in different ways. And sometimes Himalayan salt, Himalayan pink salt. Yeah, beautiful salt that is appropriate to what it is you’re trying to do.

And I’ll just tell you an aside—when I was traveling with a friend, I just made these little sandwiches with cut tomato, a little olive oil, and salt, and they were so delicious! And it’s just like, the tomatoes I had overseas are not the tomatoes that one can easily have access to here in the States. I had thought, “Oil is oil”—and you know, all olive oil is not really olive oil. Which I didn’t know, you know? You can make really wonderful things with simple, simple ingredients.

Ellison: Your poems speak powerfully on American and immigrant relations. In your poem “Redeemer,” you write “I was my life. It meant that I was hungry. / I was stopping myself in the streets and I said are you hungry.” To conclude our interview, in what ways can we feed and nourish each other better? What are you hungry for?

Gambito: Cultivating a real curiosity for the other and an excitement in that curiosity. I’m hungry for new ways of reconfiguring artists and audience. For instance, when one is a poet they write a poem, and they’re assuming somebody’s going to read it—hopefully [laughs]. But when you’re a cook, and you’re making food, and somebody’s going to eat it—the relationship can sometimes feel a lot more direct, right? Like, “I made this grilled cheese for my son. Is he going to eat it? Yes or no?” There’s this idea that each is just as important, you know? Like, if I cook all this food and nobody eats it, what have I done?

And I’m really thinking about what effect I want my poems to have in the world. What are they doing? What do I hope that they’re doing, and how do I consider an audience experience, and how can I make that interactive? For instance, I wrote this one poem called “Grace,” and what I do is I have everyone close their eyes, and we say grace in the sense that I read the poem to them. I feel like we’re in such tumultuous times right now, and we need to uphold the linked roles of artists and audience—so how do we activate each equally, right? I’m less interested in the how the artist performs, where there’s this sort of passivity in the audience—not that that’s not a lovely thing, it’s a lovely thing. But I’m interested in how you get the audience to act towards, in some ways, what it is you’re doing.

What I’ll say is that when people buy the book, or they say they love the poems, that’s wonderful and I really love that. I also really, really love when people say, “I’m cooking from the book! And here are pictures of what we made!” A friend of mine just taught this poetry class and he said, “For the end, we’re going to make dishes for each other.” That in itself—what we say can make it into the world in an incredibly rich way.