Listening with Joy Harjo

On a humid afternoon at the end of April, I sat down with poet, author and musician Joy Harjo to talk about writing. A member of the Muscogee Nation, Harjo is the first Native person to hold the position of Poet Laureate of the United States. When we spoke, she was about to wrap up her third term and had been traveling. We only had a few minutes to chat before she was scheduled to teach a Master Class for MFA students and she told me she was tired and jet lagged.

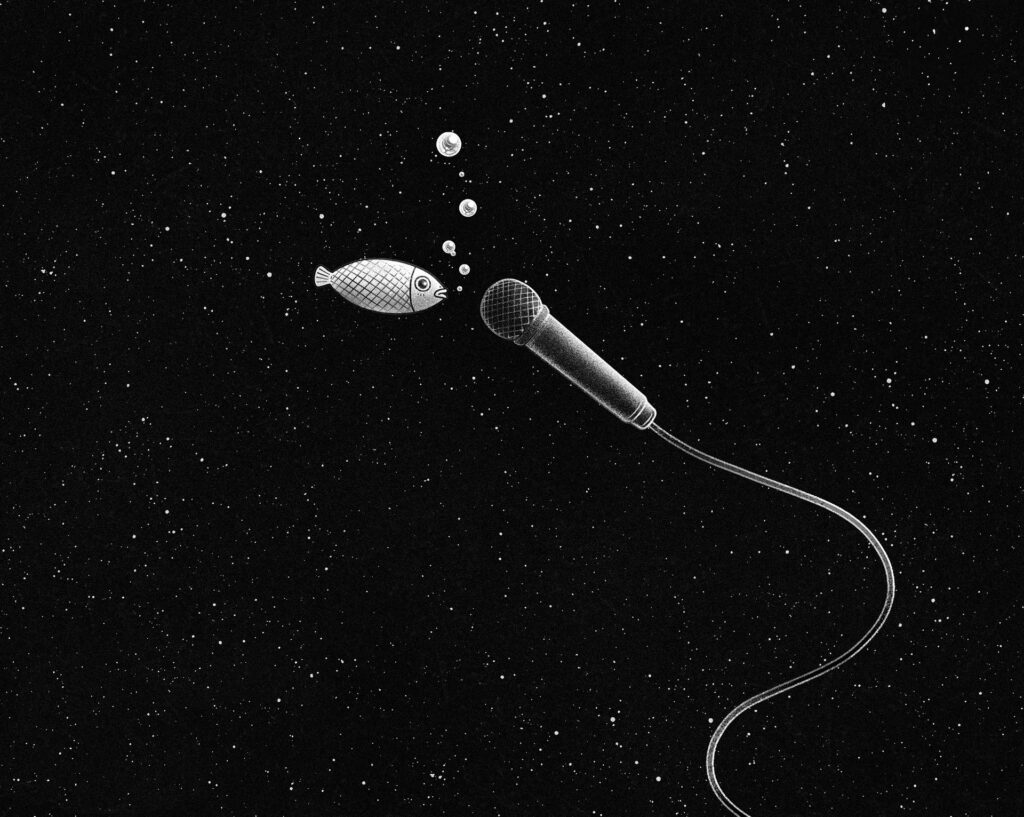

Harjo recently released a new record, I Pray for my Enemies, as well as a new memoir Poet Warrior, which blends prose with poetry and song, a council of voices in chorus. As a musician and poet myself, I wanted to talk about the Venn Diagram of her work in poetry, music, and memoir, how those genres inform one another and where they overlap. Right after our conversation she began her master class by telling us a story about being at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the seventies where the popular opinion was that poetry was sacred and shouldn’t be defiled by music. While she was there, the poet Robert Bly came for a reading and performed his work with drums, and she found herself drawn deeper into the poetry through the music. Later in the class, she sang her poem “Grace” a cappella.

Harjo’s face is tough to read. She’s quiet as we sit down at a small wood table on the screened-in porch, wrapped in the white noise of traffic and grackles. People arriving for the class are talking in the courtyard as I set up to record our conversation. “Hey, we’re recording in here!” she yells out through the screen. She laughs, momentarily breaking her sober expression and we talk.

Daniel Pruitt: I want to talk today about some music stuff. You just released a new record I Pray for My Enemies; it’s the first one in ten years or so. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the process of writing and making that record?

Joy Harjo: Usually when I do an album, I do ten tunes. My co-producer Barrett Martin usually does twenty to thirty songs on his albums. I had a lot of them ready and then we went into the studio and did some of those. The ones with me just reading poetry are ones we put together in the studio. But “An American Sunrise” was the first one, and I had put that one together a few years before, and a few of the others. So, it came together in the middle of the pandemic. He’s always said “I’m here if you want to do your next album,” and there’s emails going back ten years. He said, “Well, I’m up here in Port Townsend if you can get up here, we can do the bassline tracks,” and that’s what happened. Then he came to Tulsa, and I laid down horn and we did some of the voice and got some of his friends, like Peter Buck, etc., to play on the tracks. My favorite part was the mixing with Jack and Dino up in Seattle. That was cool. I loved working with him.

Pruitt: When you’re writing, what’s your musical writing process? Do you write stuff on the saxophone? I know you play the bass a little bit too.

Harjo: I just laid down my first recorded bass tracks yesterday. So I’m learning bass, but usually it’s a number of things. I’m very rhythm oriented. I often go to loops or even start with a metronome, but I realize I’ve done that with poetry all along. It’s just innate; I follow its rhythm, I get carried away with rhythm. So, the bass makes sense. And if I can learn to play and sing at the same time—I’m getting there [laughs]—it will be much easier. But I love, of course, I love the sax. I come with a lot of lines, I’m always improvising on sax, like there’s one little song on there that’s basically loops I think I recorded on my iPhone with just the sax.

Pruitt: The phone is such a great tool for song writing.

Harjo: It is, in all kinds of ways. I might perform one-off of some loops. I don’t have all the arrangements yet, but it’s for a song from the poem “Remember.” I’ll be doing it next Thursday night at the end of the Poet Laureateship. So, I’m working on that, and that’s been put together with a melody I found for the song. It’s like writing anything, it’s a process, and I had different versions. I even started on a version ten years ago and it was too…. I don’t know, it sounded too New Agey, which is not my thing. But I found it finally, you know how you can dig and dig, and you put it away, and then it just lit. So, it’s exciting.

Pruitt: It feels so good when that happens.

Harjo: [laughs] When it’s there, when you find it. So, I’m probably about as excited with this song as I was about “An American Sunrise,” which is my favorite song on that album.

Pruitt: It’s so good! So, you’re saying that a lot of the horn on the record is improv. That requires a lot of listening—improvisation is all about listening, right? I feel like in your new memoir Poet Warrior, there’s so much about listening. About listening with the body. Could you talk about that a little bit? What that means to your writing, both music and poetry?

Harjo: I think it’s all about listening. Probably everything. If you look at, you know the story of any scientific discovery is basically looking at data and listening. Listening to what’s coming in and configuring, but a lot of the major “discoveries” often come from something unexpected or something rising up that you wouldn’t have found without all the other stuff, because it had a way to walk into the story. It’s like when I was writing Poet Warrior, and I was writing along and then the line comes, “even the monster has his story.” I sat there for a while and I thought, and I said, “thank you,” you know because, where do these things—where does this come from? These kinds of insights. The same thing happens with music too, like finding just the right rhythm, or tracks needed to build the song on.

Pruitt: Yes! I was thinking a lot about how the saxophone—and I think you even talk about it in the memoir—is very human voice-like. If you think about saxophone lines and phrases, they are as long as you have breath for, and that’s like poetry in a lot of ways.

Harjo: It is. It is, and it’s a studied thing. I could not—like a rapper or somebody—I couldn’t improv poetry. Maybe I could at some point, but the idea of doing that terrifies me. Whereas, with a horn it’s a little different. But it depends on the configuration. If you’re on, you’re on, and if you’re off then you have to pretend that your off is your on [laughs].

Pruitt: Do you ever get that feeling when you’re sitting down to write?

Harjo: Yeah, well, I don’t always know, I don’t know where I’m going. So in a way, it is kind of improv, but I go back over it and revise. I think the same thing with improvisation because what comes out is all your practice, what comes out is what you’ve been listening to. I think it’s similar, but what is it? What do we listen to? I think there’s different layers of ears. We can hear the wind right now, we can hear those guys talking over there, I hear your voice and then there’s another layer of ears, and another. It’s like being out at Bill Johnson’s ranch and coming up to this place where it’s not a cave but it’s this area where you can tell people camped, tribal nation people, because it’s a natural place. I felt so many layers, I was listening with other kinds of ears. I was saying in the car earlier, I was listening, and I realized I was listening with my ears in the present and you could hear people talking and the different birds around there, but there was another kind of hearing. There was the rocks, and you could feel the really deep low voice of the rocks, and in between that I could feel people from another time, I could feel them there. There’s just so many layers. I think that’s what artists tap into whether you’re a musician or a fiction writer or a poet. You’re listening, and it’s deep listening. And then taking the tools you have, whether they are words, phrases, paragraphs, dreams and construct. Using those tools to construct something.

Pruitt: You also talk about the idea that poetry and writing is trying to get at something that is beyond language, which feels like what we’re talking about here. It’s interesting, I was reading a book about the human brain and one of the theories about how our brains evolved is that language came later. So our first form of communication was singing; we would sing to communicate before we had language.

Harjo: That makes a lot of sense because if you look at the roots of poetry—the oldest forms—they all go back to singing.

Pruitt: I want to talk about the anthology too, When the Light of the World was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through, and I love how you’ve broken it up geographically. There’s an interesting part in Poet Warrior as well where you discuss your internal compass. This idea of maps and directions, I wondered if you could say something about how that influenced the way you put the anthology together and how it works in your writing?

Harjo: Well of course, one of the biggest questions when you do an anthology is arrangement. The material and arrangement. Rather than go by state, because we didn’t want—we were here before there were state lines and before there was a line between Mexico and the U.S. and Canada—we knew ourselves by the land and our relationship to where we lived and often, our story roots went deep into those areas. There are so many tribal nations, over 573, I think, federally recognized and there are others who are state-recognized who are legit and some not. Some are just imaginary [laughs]. Somebody’s out-of-control imagination. So, we decided to divide it by geographical area, and I think it worked pretty well, except the areas are huge and the tribal nations within each area can be so diverse with language and so on. I think given the parameters of what we had to deal with, first it was three hundred pages. It was like, wait a minute, for this? So, we got it up to four hundred, a little over four hundred. I think given all of that, it was the way to work best. We could have gone chronological, but I think what we learned was, we saw how colonization worked and impacted each area. Because we are speaking mostly in English, or there’s translations, and so it becomes a sort of call and response in a way with the influences of colonization. You see how different it is, and even in the poems you can see how the natural world is in relationship with it and the kinds of environment. It’s very different if you live up in Alaska, your relationship with the sun. I remember standing in downtown Anchorage really early one morning—well it was not early, it was ten a.m., but it was still dark—thinking, “I am a sun person [laughs].” Our philosophy, our cultural being and philosophy as Muscogee Creek people would not work up here in Alaska because so much of it is based on the environment, even New York. New York is a cultural entity; its identity and its roots are based on urban madness [laughs].

Pruitt: Did you say that your Laureateship is about to wrap up?

Harjo: Yeah, next week.

Pruitt: I’ve heard you say when asked what your goal as Poet Laureate was, that it was to make sure that Native voices were heard and that Native communities were recognized as people. Is that in part, what the anthology is doing?

Harjo: Yeah, that one was already in motion before. Then I have another anthology that came out that is the Poet Laureate project, Living Nations, Living Words. That was a smaller anthology, forty-seven contemporary poets.

Pruitt: Well, I think we’re running out of time. There’s not enough time to ask you all the things I want to ask you, but looking back on your time as the Poet Laureate of the United States, what are your thoughts?

Harjo: You know, that’s what I’m supposed to be working on right now [laughs]. I have to give my final thoughts. I think this poet laureateship was unusual: One, it was groundbreaking because I was the first Native person as U.S. Poet Laureate; two, we’ve been dealing with a pandemic through most of it, and a racial—I do this in every interview, there’s a word I’m trying to find that I haven’t found—it’s like there’s an illness, and it burst. We’re seeing that in this country. We’re at a time when there’s this reckoning, a kind of cultural and racial reckoning going on in this country. It’s racial and also sexual; over women and then over sexual identity. So, all of this is coming—and then climate change—all of this, all at once. So that characterizes my poet laureateship, but I think what I’ve learned is how—I mean I knew this—but I’ve experienced how poetry has been there for the people through all of this. The poetry websites have seen immense readership because people come to poetry the way they always have, at times of transformation; that can be births, deaths, that can be falling in love, that can be having your imagination opened by seeing wildflowers.