she will not die laughing"

From “Peach Fuzz” by Shams Alkamil

Field Notes,

As I started college—and as my frontal lobe began cooking on high—I pulled Why Clichés off of Amazon for almost two years. I was horrified at the idea that I had undertaken a project relying on expertise at such an early age. I ended up privatizing the book after rereading it and being repulsed by how mean it is:

Field Notes,

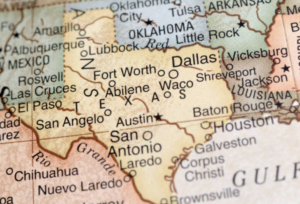

Either way, I’ve always considered myself a Texan. I like a good steak, my dad worked on his family’s ranch in Juarez and knew how to butcher any kind of livestock, and I proudly stood to chant the Texas state pledge every school day from 3rd grade into my senior year. On the other hand, I never learned “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” What was the point when I lived on the thumb?

Field Notes,

I’ll admit, some of the modern book cover trends are not my favorite, but now I see them with more positivity. They make me consider the new readers— the ones stepping into the literary world for the first time.