The Anatomy of a Boy Who Never Became a Man

“And the word became flesh and dwelt among us.”

—RSV-CE Bible, John 1.14

DEFINITION

It was a cold night. One which, like the many others preceding it, had left the boy nestled in bed, his face aglow with the fluorescence from the phone in his hands. He’d shut the windows and dropped the curtains a few minutes earlier, after the breeze blustered in, sending drizzles, and the moisture clung to the dusty window net onto the floors, where they became a colony of filth. He was too tired to walk to the kitchen to get a mop, so he’d let the mess lie there, hoping that by morning it would have disappeared, and if Jesus was as kind as His ambassadors claimed, then perhaps He would intervene, drying it up completely, leaving no smears or smudges. For the boy feared his mother, and all the things she screamed and did whenever her affairs weren’t as she intended them to be.

She was once an ambassador, too, this fearful mother. At around the time the boy’s father was still alive. She only knew two things: God, and every other thing He willed her to know. She would wake up at four in the morning, pray her rosary—because she’d grown up Catholic, and wasn’t sure how to detach completely—then, roaming from room to room, she’d spring open her children’s doors, sprinkling water on their faces, parting their curtains to let streaks of sunlight in, all the while her hymns never halting. Everyone in the house would join her in the dining, the makeshift praying room. Then, making her four children and two house helps stand, as they couldn’t sit without dozing off, she would force her Igbo choruses down their throats like chunks of eba, expectant of melodies from their lips. Like she was directing a church choir, and not six sleepy kids, none of whom were, at the time, up to eighteen.

The boy, the third of the four, and the only son, was the apple of his father’s eyes. If he grumbled, his doting father heard, even from thirty miles away in Nnewi. If he was bullied at school, his father shed his usual timidity, confronting the principal and intimidating the teacher until the bully relented. And when he refused to lead prayers—which was every time it was his turn—his father took up the mantle, praying in his place without complaint. Little did he know that the boy was slowly cultivating an aversion to prayer, loosening his grip on faith with every unsettling devotional they read together: the famines, the plagues, the wrathful infernos. Until the moment he realized he didn’t know how to pray, as he sat by his father’s hospital bed, his hands clasped, his mouth agog, only for the word “gosh” to escape it like fleet-footed flatulence.

If the boy were to define himself, he would begin with any moment that happened before that day. He’d tear out pages from his kindergarten years, when the room was filled with water guns or Bakugans, yet he gravitated toward crafting dollhouses and grooming Barbies instead of rampaging the air with action figures. He’d recall primary school too—how, back then, he wasn’t sure who he had a crush on, but knew he felt a deep, unspoken kinship with the girls, something that never existed with the boys. And maybe, just maybe, he wouldn’t forget when he stumbled upon the word. In his first year of Junior Secondary School, as the umpire of the spelling bee threw it at him in a clinical haste. Transgender. He’d made nothing of the uproar that skirted from one end of the hall to the other as he grasped the microphone and made the attempt. In truth, he even found a thrill in the moment—not least because he wasn’t sure, thanks to the umpire’s muddled pronunciation (a slurred g that sounded like sh), whether the word was transgender or transcender. But the chatter in the hall muffled his acute, girlish voice, so as he raced through the letters, slapping his thigh like Akeelah, there was no interruption, no “come again,” just a light applause, and this uproar that had refused to dial down.

All these experiences he would say defined him, but most concretely the third. Because as the boy got down from the podium after tanking the next word, colloquium, he’d settled into the nearest bench he could find, betwixt some nitwits who pointed and laughed and called him this word: transgender. Before that day, he hadn’t a clue what it meant, and from their moronic gesticulations, neither had they. There was a dictionary on the table before them, and curious to know why they laughed, he grabbed it and scrambled through its scrunched pages. And on getting to the word, he froze, for he hadn’t realized before then that there was a word out there that described how he’d always felt on the inside.

transgender /tranzˈdʒɛndər/

adjective (not comparable)

denoting or relating to a person whose gender identity does not correspond with the sex registered for them at birth.

ORIGIN

I.

The boy, unlike most of us, beat himself up, wondering where he came from. Was he a spineless excuse of a man because he abhorred smelly, clustered places and wasn’t a fan of gruesome fights? Was he a curse from the pits of hell, like his mother insinuated on the night of his father’s burial, because he wept shamelessly, and wouldn’t leave the grave, despite how threatening the skies had become? Or was he truly Ifesinachi as his father had fondly called him? And what if he wasn’t, would that mean he hadn’t emerged from God, like the name suggested, and was a rather cursory afterthought—a quickie no one had bargained for?

On that cold night as the boy curled up in bed, his mind swarmed with these theories. But they hadn’t sprung from nowhere. Like most premeditations, they clambered into his brain and etched themselves on either of its hemispheres, meandering to his forethoughts when he’d just been earnestly provoked into questioning himself. For if it wasn’t his mother yelling into his face, challenging his masculinity when he wasn’t able to start the generator with ease, it was something else, someone else perforating his mind, filling it with these tainting thoughts.

II.

The boy originated from Awka, where the roads felt more like rutted labyrinths than paths, interconnecting destinations to origins. Where bridges housed cluttered kiosks and indigents, so you weren’t sure who chanted and tailed you—a money-hankering merchant or a scrawny, one-armed youth—yet you walked ahead, a prudish smile spread across your face, clenching your belongings, lest they evolved into larcenists, steeled with a knife and mounds of juju. Because this was Awka, where anyone desperate to be someone had to be more than one thing.

The boy’s father embodied this perfectly: an exuberant man who wanted nothing but the best for his family. Before he was a pastor, he was a banker, and even after he began shepherding an entire parish, he remained both. He couldn’t bring himself to resign the very month whispers began to circulate about his potential promotion to branch manager. Coincidentally, that was also the month the senior pastor above him was transferred to another parish, and he was elevated to take his place. It was the month the boy was happiest.

He was thirteen at the time, and although he hadn’t experienced this peace and joy the advent of money brought, he’d heard about it in the stories of others and had seen it first-hand in his tall, long-jawed friend: Noel, who went from wearing damp uniforms because he had only one set to being dropped off at the school in a Jeep the size of three elephants’ arses. Then, they’d said Noel’s father had begun a Ponzi scheme, where he called his business partners whom he robbed blind clients, and they said they’d known this, because it was only natural to amass the kind of money he did in that timeframe if he were Ibeto or Tonimas. And, since he was neither affiliated nor related to either of them, he had to be a maga, a swindler.

But the boy did not care for these stories. If anything, it was their mutual ostracisation that tethered them—nothing more. They’d met on the assembly ground on the first morning he had forgotten to put on socks. In their secondary school, this came with the punishment that while other students stood in queues, the perpetrators would kneel at the corner of the podium, from where the principal addressed them, so all students could see them. The boy was so humiliated that he wanted to cry, and maybe if Noel hadn’t nudged him when he did, he might’ve.

“So, you decided to join us today, eh?” Noel said in a suave countertenor, laced with that unmistakable Igbo cadence the boy could never confuse for anyone else’s. The voice echoed in his head, clear and familiar, but he didn’t respond—not even with a shake of the head—too mortified and afraid of drawing attention to himself. It was his first time being flogged in public, and he’d tried hard not to make a scene. Though the strokes burned like fire across his butt, what seared deeper was the silent accusation—transgender—a label that felt like a trap closing in around him.

So he shut his eyes, clenched his jaw, and stiffened his body, holding in every cry, every gasp. He couldn’t let it become a thing.

Later, as the students filed into their classrooms in neat lines, he returned Noel’s nudge. “How did I do?” he asked, his voice barely a whisper, eyes rimmed with unshed tears. Noel glanced at him—just a beat longer than necessary—as if trying to place this strange, arrestingly beautiful boy. Then he smirked, a flicker of something playful in his eyes. “You did just fine.”

Their school was a monument in their society. One of those historic missionary schools that predated many of its teachers, producing the best results year after year, scattering alumni across the globe like mustard seeds and graduating valedictorians who, without fail, left the country before anyone could utter ja—. The boy’s parents had been crestfallen when his older sisters failed the common entrance exams, but when he passed, their joy was uncontainable.

The path leading up to the school was narrow and noisy, with beggars and peddlers crowded at every stop, banging their wooden platforms, crooning praises for money and patronage. This gave the route an unseemly untidiness, so it was something to worry about; that amidst this ruckus, the leaders of tomorrow were being cultured. Until the glossy, black gates came into view, revealing two identical bronze statues. On his first week, the boy, with some classmates, were told by some funny-looking seniors that those statues were the replicas of the first students to be enrolled. Adam and Eve, their parents had called them. In their stories, Adam and Eve were siblings, but being the first students, head boy and head girl too, they’d acclimated into pleasuring themselves whenever they needed to, in the bushes behind their classroom; that explained the white splotches on the brown paint. Whenever the boy was in class, he would imagine Adam, restless, stripping his plaid blazers and lampblack trousers, tearing apart his cream T-shirt and Ben Ten boxer briefs, lifting Eve’s pleated skirt, hurriedly, before the teacher walked in. And he wouldn’t stop imagining and wishing he were Eve—lucky Eve, who got her ass split open like hot agege bread—even after the tale had been disproved.

The statues of Adam and Eve, apart from the entrance, were at the centre of the classrooms, bordered by lush dracaena shrubs in flower pots and a shit ton of spear grass; a textbook in their hands, a pencil tucked behind Adam’s ear. Visitors always stopped to admire the view whenever they toured the classrooms, including the boy’s parents. Once, at the start of the boy’s midterm break, they’d followed the gravelled roads, aimlessly caressing their hands over the trimmed hedges like stoned teenagers, till they were stopped by a security officer. They’d reached the spoors of aged kola trees that artfully paved the way to the hostels, and they cooed, taking the delightful sight in.

But they had no clue that beyond there, the hostels were marked by lichened fences and rusting gates, sodden drainages and untidy quadrangles, slimy sheathings of spirogyra lacing the tap intersections where the students washed their clothes and quenched their thirsts via their hands after a paltry meal. Sometimes, the flurrying air carried the smell of sweet-scented soap and fried akara; other times, it reeked of urine and mottled feces rising from the open gutters that doubled as latrines after dark. Yet, in the nucleus of all this squalor, there was a spot where the breeze was tender and the air pleasing; where the crickets sang and the stars twinkled like lanterns squinting from the skies. Behind the clinic, under the Neem trees, where the boy and Noel shared their first kiss.

III.

The boy couldn’t bring himself to tell anyone about Noel and what existed between them, no matter how deeply he longed to. So he wrote—pages upon pages—about everything he did, everything he felt, and everything he wasn’t permitted to become.

That was how his eldest sister stumbled upon the pages where he described, in aching detail, the thrill he felt from the helplessness of choking on penises—Noel’s own, to be precise, that curved like a boomerang, and his current lover Sahad’s, which tasted like coffee on a slow morning—the dizzying surrender, the blur between pain and pleasure that made him feel, if only briefly, startlingly, unbearably alive. And that’s how she told his other sister, propelling the revelation until it travelled, quite daringly, like the gospel, settling in his mother’s ears on this cold night.

But unlike a horrid news headline you refuse to believe, it was neither rebuked nor relinquished with the blood of Jesus. Singing mother simply stood and strolled to her room, leaving the boy to wonder what would eventually become of him in this little, scrambled Awka, now that it had become too certain. What would become of his body; this holy vessel, this royal priesthood, if fearful mother was to ever find out about the transitioning it would undergo?

And so, he left the house the next morning, just as he came into this whirlwind of a world—with nothing.

MORPHOLOGY

I.

At birth until he turned ten, the boy resembled his mother. Fair, pretty, with lashes that grew thickly like a horse’s tail, yet were feathered unlike anything you’d ever see. His eyes were taut and shrunken so it seemed as though he was always drowsy, like he could barely see. His nose was thin and prominent, delicately faultless. His pink lips puckered when he smiled and so he always smiled, even when he cried. And he was slim; not so slim that the wind could carry him, but just enough for the house helps to call him a broomstick.

So, with every one of his sisters’ pageantries he attended, likewise every beautiful boy comment hurled at him in the market square, he glanced at his reflection, and saw a body begging to be fashioned.

II.

There was no need for the face primer, and the blush, and the contour, and the concealer, and the highlighter, and the liquid foundation—at least, not before the pimples. But with the pimples came the jut of an Adam’s apple where a soft boy’s throat had once been, and it begat a foliage of hair above his lips, creeping over his cheeks, wrapping around his chin like moss on walls. And a strange awareness seeped into him like the shiver of a fever. He couldn’t let his body morph beyond recognition.

It was in Noel’s home that he noticed how much shame he had buried in the quiet chambers of his heart. They were thoroughly unclad under the sun, by the duck-shaped pool, staring into each other’s eyes. All for the boy to rise and wrap a towel tightly around his chest.

He couldn’t explain this feeling, this discomfort that dug a home in his chest with each second Noel lustfully glared at him. He’d been naked in front of him more times than he could recall, but never had he felt unattractive or unworthy of being wanted.

“What’s the matter?” Noel raced after him, asking. He hadn’t bothered with a towel; he let all of him bask in the blazing sun. His biceps, his chest, his bulging boomerang. The boy had never noticed how confident Noel was until now, and it irked him—all of it.

He shook his head as a reply. He’d been speaking less ever since his voice had splintered. He’d been walking like he was afraid of falling. Had Noel been too self-involved to notice? He wanted to pick a fight; he almost did, but then they heard the thwack from the guest house. It sounded like a balloon or a bird splattering or crashing into the glass windows, and they raced toward the direction of the sound, subtly hoping it was the latter in the guileless way of children, so they could watch the hurt thing regain consciousness and take flight as though nothing had happened. But when they arrived, there were shards of glass on the rug, and on the couch there was a brick the colour of blood with a note that read: Vamoose, onye wayo!

It all felt a bit too theatrical, but that night (as the boy would later hear from someone so forgettable they might as well have never existed), Noel’s father stumbled back into the mansion with a bloodied head and bruised arms, limping as if he’d soiled himself. His trousers sagged, barely clinging to his waist, and his eyes were etched with a fear so raw it seemed to unspool every lie he’d ever told.

The boy’s flat chest heaved as this person spoke, and his first thought wasn’t whether he’d see Noel again, whether their paths would ever cross—but about how Noel would always remember him from that afternoon: dainty wrists, pimply face, and all.

III.

The boy traced his fingers over his skin in the way he saw the ladies in the commercials do. Sensuously, carefully, like any pressure would till his skin and give way to pores that would erode the glow he’d struggled so hard to cultivate. He observed with the fastidiousness of one who was newly obsessed, taking in the softness and this newfound suppleness that had come to be in the last couple months, marvelling at the wonder that was the effect of the estradiol shots. And so, it wasn’t until later that night as Sahad made love to him in the lavish, melodic grace ascribed to foreign indie films—holding his gaze as though it were the very reason he existed—that, for the first time, Ifesinachi truly felt like a woman.

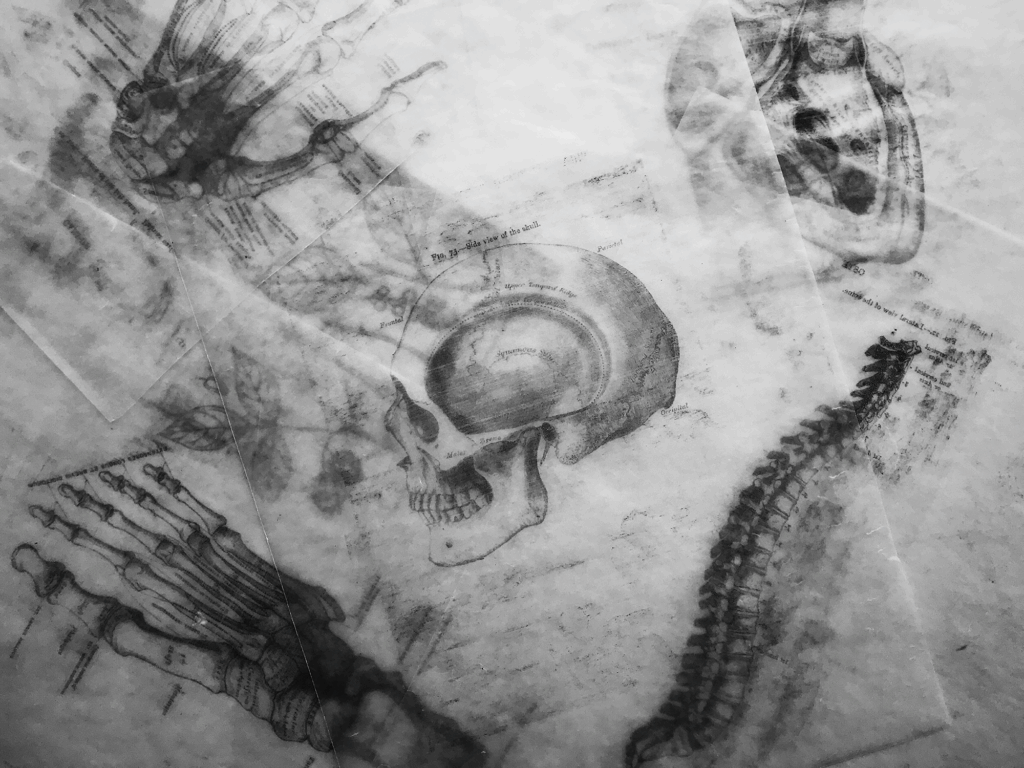

DIAGRAM

Figure: A Well-Labelled Diagram of a Woman, Who Was Once a Boy, Carefully Outlining Her Bruises and Contusions: A Stitch in Her Jaw, a Blot Between Her Breasts, Cicatrices On the Delightfully Glacé Skin Swathing Her Femurs and Glutes. Eyes Hollow, as if Hiding. Palms United, as Though In Prayer.

BLOOD SUPPLY

Like all remarkable targets—a piñata, the side of a defective television—Ifesinachi was struck. A blow to her lip, a punch to her side, a whack at the back of her head until all she heard was a chorus of clashing dins. And much like those targets, after the striking, she swayed in the direction of its blows, or on the days she felt strong, remained affixed to a point. If it didn’t hurt so much, it might have been poetic: the way the pain returned in loops, slow then sudden, dull then piercing, always raw, always reluctant to leave. And maybe it was a little, as pain in itself could be romanticised and, for the intent of survival, perceived to be this sweetly scathing thing. But as Ifesinachi picked herself up from the tarmac, coughing up blood, her vision blurred, none of that mattered.

She imagined the boys giggling, flailing their knuckles to dilute the sting in them, their chests heaving with gratification, and couldn’t wait for her father to appear by weekend when he’d hear everything.

She limped to her school guardian’s office, pigeons flying in echelon overhead, and—because it had become so routine, like digestion—she settled behind his computer, waiting for his phone. Like a wooden figure, he entered with it: his jaw slack, his eyes sunken. But instead of her father’s familiar, sunny chuckle, she was greeted by the sombre voice of her eldest sister. There wasn’t much to say. Their father had just had a heart attack.

VENOUS DRAINAGE

I.

Rage, a self-consuming corporeality, collared her when she least expected it. At the funeral months later, tunnelling through her veins, it made her thoughts turn, without rhyme or reason, despite herself. And she screamed, pummelling the earth atop his grave with a strength she didn’t know coursed within her.

Relatives, with whom she shared a genealogy as convoluted as the small intestine, sighed from calculated distances—arms crossed, heads bobbing in pity. When they noticed she was alone, they seized the chance to approach, to tell her that everything would be alright. But it was a thing people said; whether the statement itself offered any assurance was besides the point.

Ifesinachi didn’t hear shit. Coiled like a foetus on the soil, her thighs to her heart, she had never felt so afraid, so alone. More than anything, with a sensibility that burned like fury and submerged like water, she desperately desired to be someone else.

II.

The acceptance, rather than the fear of her rage, was the beginning of wisdom. For in the times before Noel, and even after him, letting her emotions get the better of her was never an option. She’d learned to exist in the manner that would be tolerated by others—lowering her voice to a rougher register, walking with squared shoulders, keeping her hands out of expressive gestures. Never being flashy, feminine, delicate. Lest she risk sticking out like a fish out of water. So maybe it was simply fate that she was coming to this realisation, right when the man called her a slur at the buka where she ate.

“Hey you! Mannerless person!” He turned back, and she held his gaze. In a voice that sounded alien to her, strong and without a stutter, she said, “How pathetic and sad do you have to be to insult someone you’ve never met?”

The buka grew silent, waiting for him to react. Perhaps he needed a translator. Perhaps his tongue got caught in the crap he let fly out of his mouth. But as was expected from a man with a big body to make up for every other part of him that was small, a punch was hurled. And following closely, igbotic ululations, loud and in dire need of rhythm, flew into the air. Still, it was the man behind Ifesinachi that held his eye. The man who, because of how often he frequented the buka, got the owner to send the mannerless person away, his money returned. The man who, after three Thank You‘s plus one How’s your eye? introduced himself as Sahad.

And like most romances that bloom under the clemency of the sun, the rest was history. Their first date, arranged after three weeks of incessant texting, was at a restaurant so fancy she had never even imagined visiting. Szymanowski’s Violin Sonata in D Minor drifted through the air as they walked in. She took in the chandeliers, dripping with crystals that cast scintillas of light across the room, and the walls adorned with tasteful, moody artwork. Perhaps it was this breath-taking ambiance, but she couldn’t shake the feeling that everyone was staring. Was her jaw shaped like a man’s? Were her pits sweaty, her palms dry? Did she look absurd teetering in those heels? Her thoughts might have gotten the better of her had Sahad not smiled and ushered her into her seat, his voice laced with the playful tempo of a risqué allegrissimo.

They talked about what they’d been through, each of them taking caution in sharing, as to not overburden the other. With practised ease, they dug their forks into peas and cauliflowers, cut through shrimp and tenderised meat, the flavours melding into their tongues as if bursting into song. They shared what they’d hoped the future would bring, and as they walked back to Sahad’s Lexus, their hands intertwined, nothing else mattered. Except that one person who’d been watching.

“Sinachi!” The familiar voice pierced through the night, and drew raindrops. “So this is what you’ve been doing since your father died.”

And like clockwork, Ifesinachi, dazed but not entirely taken by surprise, glanced over at a staggered Sahad, as though apologising for the side of herself she was about to reveal.

NERVE SUPPLY

Quite akin to the femoral nerve, which, after a short course, divides into two branches, the woman had two prime encounters that enervated her:

I.

For in the beginning, there was the cold night. A day which had begun, rather auspiciously, with the date she’d been looking forward to. A day that taught her to make things happen, instead of waiting around for stars to align.

She withdrew her hand from Sahad’s on hearing her name, and as her mother inched closer, Ifesinachi’s boldness revealed itself like a second skin— slick but firm—steadying her as she stood before the woman who had birthed her.

Those stars, the incandescent lot, bore witness. There was a wild edge to her voice as she beat her chest. “Why is it so hard for you to accept me as I am? Aren’t mothers supposed to protect their daughters, not become the very troubles they face?”

“But you’re my son! With your father gone and you this way, who will protect me?”

For the first time, Ifesinachi really looked at her mother—not the woman who had loomed over every decision in her life, but someone who now appeared fragile.

“Mummy, I don’t know.”

Ifesinachi stepped back, slowly, deliberately, leaving her mother standing there, unsheltered beneath the streetlight.

She blocked every other sound there was and watched Sahad slowly walk to his car, wondering whether this incident would be, for him, a deal-breaker. In her chest her heart hammered so hard, as if asking itself the same thing. But when he waved, smiling, offering no questions, only understanding, it stilled.

She walked home with only the rainstorm for company. It was poor company—soaking her clothes, ruining her makeup—but at least it made no demands, letting her thoughts twist and churn in ways they never had before. She knew then: she couldn’t stay in her mother’s house any longer.

And so, later that night, after rehearsing the words in her head, she called Sahad—voice low, unsure—and asked if she could stay with him, just for a while.

II.

The woman Ifesinachi—a devout agnostic, if such a thing were possible—embarked on a search for community, though she’d never admit it aloud. Maybe it was for the thrill. Maybe for meaning. Or maybe she just needed to feel less like a question mark in a world constantly exclaiming. She turned to social media like it was a religion of its own, one she could curate: waking up to strangers’ sunsets in Santorini, ignoring sugar-laced DMs from married men with God-fearing bios, dragging misogynists by their poorly punctuated tweets. Feminism, for her, wasn’t about rage or resistance. It was about clarity. She didn’t hate men—she just wished more of them would lay down their armour, hush their egos, and listen with the urgency they reserved for ball sports.

They sat cross-legged on Sahad’s floor, knees grazing, the scent of their dinner still clinging to the air like perfume. The fan spun lazily overhead, humming a tune only the curtains heard and obeyed.

“Ifesinachi,” he said, her name cautious in his mouth, “can I ask something without sounding like one of those men you roast online?”

She turned, her brow arching. “Depends. Are you about to say something stupid?”

He laughed—light, the right amount of nervous. “Maybe. But… how do you know it’s abuse? Like, where’s the line?”

She stilled. Not from offence, but from the weight of the question. And the way he asked it—not as a defence, not as a trap, but like someone laying down their weapons, eager to be taught.

“Because I’ve lived it,” she said, voice quiet but unshaking. “Not always directly. But in stories, in silences. It’s in how a woman laughs too softly at a joke that isn’t funny. Or clutches her keys like a weapon when walking past a group of men. It’s a hundred things that accumulate.”

He nodded slowly, like each word was folding into him. That was what she liked—how he listened, not just to respond, but to carry. Like water, taking the shape of what she poured into him. If she texted, he was there, hands poised to help. If it was a phone call, he picked without delay, wheedling until she’d said her mind.

So when he suggested the move to Lagos later that day—her fingers curled around Sefi Atta’s Everything Good Will Come, its sentences curling into her skin like prayer—she watched the slope of his shoulders, the hush that settled in his chest. He’d already made room for her; she could feel it, like a light left on in a room she hadn’t dared enter. And so, with the poise of someone reaching for a glass of water, she said, “Funny. I was just about to say the same.”

It was in Lagos that she attended the ball, with its sultry music and salacious airiness; an intoxicating brew. There, she met Iruo, all striking beauty and rapturous rhythm, hips swaying as they approached and said something she can’t quite recall, though she remembers laughing. Through Iruo, she met Aira, who through tireless advocacy for trans rights knew the right medical facilities to get a trachea shave or laser hair removal without falling into crippling debt. At twenty-seven, with a political career in full throttle—whatever that meant for someone deemed ‘non-existent’ in a country obsessed with policing bodies—Aira organised rallies and gatherings where multitudes could be said in a silence.

Some nights, they wept over Pose and the ache of being unloved here. Each of them knowing that, in leaving Nigeria, their lives would relatively get easier. And Ifesinachi—who’d started dreaming of Bangkok clinics—simply nodded, a beat too long, weeping too, but saying nothing.

CLINICAL ANATOMY

Say, to what lengths would time have eroded Ifesinachi’s sense of self had she never found a place to belong? Would she have known the wistful ache of love if Sahad hadn’t crossed her path? Could she have stood against her mother, summoned the nerve to leave the nest? If her father had never died, would a part of her forever be missing— like the appendix, a part she’d never have embraced had it not been triggered? If there had been no Noel, would she have ever known the fleeting comfort of being desired? And if never desired, would she have been fated to live unseen and die alone?

Her hands trembled faintly as these questions, like soft murmurs, swirled through her mind. She focused her gaze on a corner of the reception, where the lights cast a dark shadow. Not letting go until the nurse appeared, a sweet sheepishness about her.

“Dr. Bannarasee is ready for you, dear,” she said.

And so, grateful for every happening that led her here, she stood, and with a smile as wide as wonder, walked forward as if, at last, the world were finally hers.