Ya’arburnee

Ya’arburnee

Arabic

yuh-ar-ber-nee

n; “you bury me;” the hope that you will die before the person you love so you will not have to live without them

On the drive home from the hospital, Esme clenches her fingers around the steering wheel and she imagines that she and Davis and their car are swept off of Lakeshore Drive and that they sink to the bottom of the lake in their decades-old Ford coffin, and she imagines that they are never found and that their bodies slowly decompose and diffuse into the water until the particles of them are spread far and wide and they are both the lake, and the lake is them, and they are both each other, and nothing will matter except that they both took their last breaths at the same time.

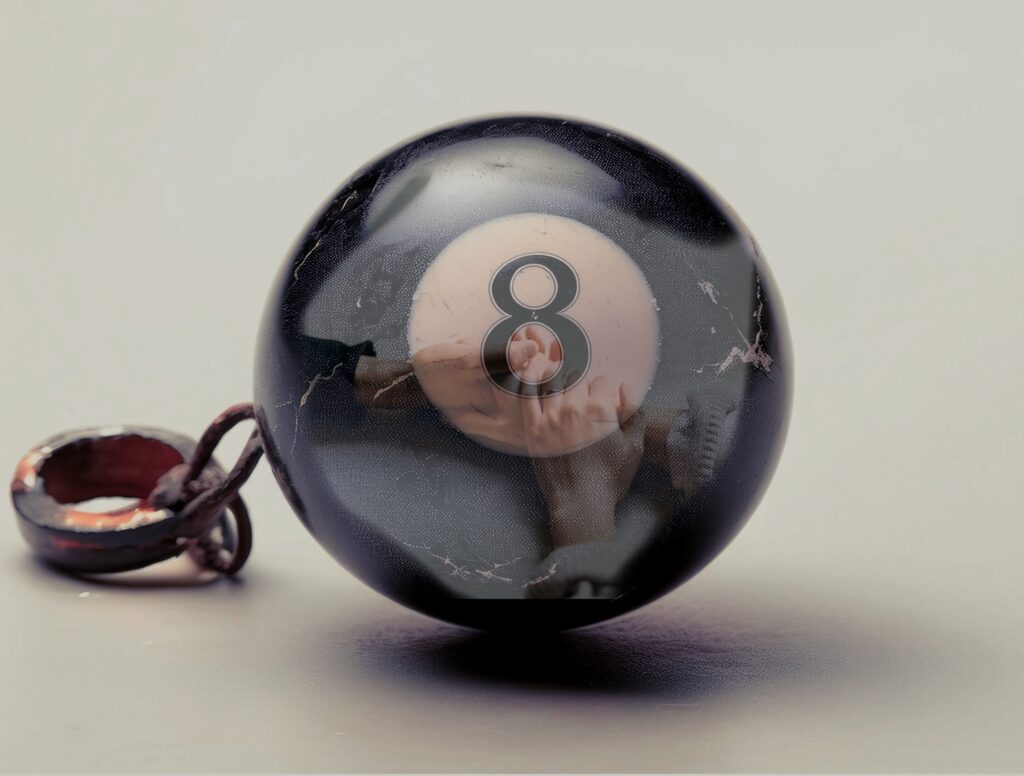

The car is silent, and it does not get swept into the lake. It arrives safely in the parking garage of their building and Esme turns it off. There’s a miniature Magic 8 Ball on her keychain that she’s had since her nineteenth birthday, and it bumps against her hand and she wonders if it’s fair to be angry that the thing didn’t warn her about all this.

The first time Davis had ever asked her out to dinner, Esme had been eager and anxious but wanted to be glib and nonchalant, so she had grabbed the little keychain and repeated the question to it, shaking and telling herself that whatever it said, it was fate. The Magic 8 Ball sent her out to dinner that night.

Davis thought it was funny, so after that they used it for every decision. Not really. They didn’t follow it blindly, or trust it completely, not when it mattered. But when it said yes, they should order Chinese for dinner, they did, and when it said no, they should not take another shot of tequila, they called it a night.

When Davis had gotten down on one knee, Esme had once again repeated his question to the Magic 8 Ball, and she shook it three times until it told her to say yes. The keychain was the closest thing either of them had to a higher power.

But the stupid thing never mentioned anything about cancer.

Davis and Esme get out of the car at the same time, and as he slams his door she sees the muscles of his shoulder shift and suddenly his body seems so there. Has he ever really been physical before? Tangible? She needs to touch him.

She crosses to his side of the car and puts her hand in his and squeezes, feeling the satisfying smooth warmth of his skin. They had started the day at urgent care. The doctor had listened to the symptoms and nodded along with a little crease between her eyebrows and then decided she would feel more comfortable if they went to the ER and got some testing done. One MRI later and they were seated in front of another doctor with the most monotone voice Esme had ever heard, like he’d sanded away all the bumps and filled in all the divots until he had a nice flat surface on top of which he could slap the diagnosis of the day and send it down the patient’s throat as smoothly as possible.

“There is a tumor in your brain,” he said in that voice, the words bare and dry like stones in a field. Her own monument of terminal disease.

Except it isn’t hers, she reminds herself as she and Davis walk to their apartment. She could deal with it, if it were hers. She could optimize her bucket list. She could adopt a dog and give it the name she’d reserved for her firstborn child that would never be. She could pick out the granite for her tombstone, curate a playlist for her funeral. She could write her own “The End” in flowery calligraphy if you gave her a good pen and a few tries, and she could die happy holding Davis’s hand.

They’re still holding hands when they get to the apartment, and Esme wonders what it’ll feel like when his heart stops pumping and those fingers—warm, slightly sweaty fingers—go cold and stiff in hers.

They pause for a moment in their open doorway, the slab of his diagnosis resting between their shoulders. It’s like stepping into a future memory: this is what their home looked like Before, and once they bring in this stone cold cancer it will never be the same.

Davis breaks away, walks toward the tiny closet that houses the washer and dryer.

Esme closes the front door with a little click and slips out of her shoes. Her socks are bright yellow on the tops, dingy yellow-gray on the bottoms. She hasn’t thought about it yet, but later, when Davis is gone, she’ll sit cross-legged on the floor, surrounded by piles of his laundry. Some of the shirts will still smell like him, and she’ll hide those under her pillow. She will wear his sweatpants to bed without underwear to feel close to him. She will keep the sweatshirts that mean something to him, meant something to him, in a pile in their closet and she’ll tell herself that one day she’ll learn how to sew and she’ll make them into a quilt. And the rest of his clothes she will pile into white garbage bags and she’ll write goodwill on the sides in Sharpie but she will never find the strength to carry them out of the apartment, and they’ll sit in a heap by the front door until she’s gone too, and someone else will have to figure out what to do with them.

Davis pulls his toolbox off of the shelf over the washing machine. It’s bulky and heavy, and he holds it straight-armed at his waist as he begins to shuffle down the hall.

“Where are you going?” Esme asks, following him to the door of their bedroom.

“I’m gonna fix your bookshelf,” he says, dropping the box to the carpet with a muffled thump. He squints his eyes shut for a moment, face wrinkling against the pain in his head that had put their day in motion in the first place.

The shelf had been rocking lately, and he’d promised to look at it. “You don’t need to do that right now,” she tells him, even as he pops the lid of the toolbox. Her heart flutters. She hasn’t felt nervous around Davis since the first few months of their relationship, when he was still a tall, dark stranger with a depth of mystery in his mind. Getting to know him had been like learning to step behind his eyes, read his thoughts as he was having them, until nothing was a mystery anymore because every crease and wrinkle of his soul was as familiar to her as his smile.

But the butterflies in her stomach now are unmistakable, the same ones she’d felt at that first dinner. Esme doesn’t know what he’s thinking; she’s been locked out, left alone with his body, skin and muscle and bone and cancer cells separating their minds.

“Let’s watch a movie or something,” she says. “A comedy. We can order pizza.” It sounds thready, her voice.

He shakes his head, removes the books from the shelf in threes, placing the little stacks on the floor all around him. He’s cross-legged, barefoot, the callous on his big toe peeking out at her. It’s all she can look at.

She sits on the edge of the bed. She doesn’t want to tiptoe around Davis, but she doesn’t want to let him out of her sight, either. Her body aches to be against his, her head resting on his chest so she can hear every blood cell leave and enter his heart. She wants their skin to touch until he goes into the ground.

Instead, she folds her feet up underneath herself on their periwinkle comforter. Their bedroom is her favorite room in the whole wide world, a sanctuary they built together four years ago. Davis doesn’t believe in minimalism and Esme doesn’t believe in monochrome, so the room became an explosion of saturated color and memories. Above their bed hangs a painting of them dancing their first dance to a Queen song, in oils of soft purple and pink. On another wall is a grid of polaroids, each dated in Davis’s careful handwriting. And on another wall, her bookshelves, which Davis had built for her with his own two hands, painted deep olive green.

Esme watches him maneuver the screwdriver with a practiced hand, tightening the screws on the problem shelf. He has always loved making things, fixing things, working with his hands. She realizes with a sinking heart that he will have to quit his job, sooner or later. A rolodex of impending symptoms cycles through her head, carefully enunciated in the doctor’s voice.

Fatigue. Seizures. Muscle weakness. Paralysis.

Paralysis. He would be miserable.

When he’s done, he picks up the small stacks of books and replaces them on the shelf, each exactly where they had been before. He places the screwdriver back into his toolbox, closes the lid. He scoots across the floor until he is at Esme’s feet, then leans forward, buries his face in her stomach. He pulls in a ragged breath.

Her body doesn’t respond immediately, like it should. Like it wanted to only a moment ago. She knows she should comfort him, but she feels frozen. Paralyzed. Haha. It’s not funny. It feels like she’s crying but the muscles of her face have not twitched, her eyes are dry. She leans forward mechanically, kisses the crown of his head. She shudders, a terrible electricity jolting through her as she realizes her lips have found precisely the patch of skull that the tumor is hiding under, and then it is here in the room with them, the tumor, the corporeality of it, and she realizes that it had been here in the room with them when they woke up this morning, it had been here in the bed with them last night, when she ran her fingers through his hair and kissed him, completely unaware that their life together was already on its way to ending.

Esme sobs. No, it’s not her sob. It’s Davis’s. She pulls back slightly, brushes his hair off his forehead and tilts his head up to see his eyes. The brown of them is deeper than she’s ever seen it, like he’s fallen down a well inside himself.

“Hey,” she whispers. “It’s gonna be okay.” Her first lie. “I don’t know what to do,” he says.

He could mean any number of things, like how do you spend the rest of your afternoon after you find out you’re dying, or how long can you keep fixing cars with terminal cancer knocking around in your skull, or how exactly does one “put one’s affairs in order” before they die, but because she knows Davis better than she knows herself, Esme knows he’s talking about the surgery.

The monotone doctor had given them a couple of days to decide on a treatment plan. He recommended an initial surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible, then a regiment of radiation therapy to try and eradicate the stubborn remains. He could get Davis into the OR on Friday. “We really shouldn’t wait much longer than that if we’re going to operate,” he had said, citing the statistics and stressing the importance of being proactive.

“I could die,” he says. He’s right. And that’s not even all the risk. He could get brain damage—speech issues, motor difficulties—and then die anyway. His lips are pressed against her stomach and her shirt muffles the words. “I could die next week if I do it. Before we’re ready.”

Esme won’t ever be ready. “Or you could get more time. If the surgery works, and the radiation. Maybe you could live a really long time, like a lifetime.” A part of her thinks that, if they buy enough time, she won’t ever have to face his death. If she puts it off long enough, she won’t ever have to plan his funeral. The more time, the more chances he lives longer than her. She could die in a plane crash. She could get shot on the street. She could have her own brain tumor, lingering beneath the surface, a more aggressive one that takes her life just moments before his tumor takes his.

A lot could happen in a few years.

“Maybe you could even live longer than me.” The last word comes out mangled, and Davis’s head snaps up, his thumb moving to wipe a tear from her cheek. The force of the love in his eyes, in his touch, undoes her, and the tears come faster, between big gulping gasps. She feels like if she opens her mouth she might unravel out of it and land on the floor in a tangled heap, but she does it anyway. “I want you to bury me, Davis. You bury me.” It comes out somewhere between a plea and a command.

Davis rises off the ground to fold her in his arms. She shakes them off. Hurt blooms in his eyes. His arms hover in the air, uncertain. “Esme?”

Esme pulls her crying under control, wrapping it up inside her with a few sniffles. “I think you should get the surgery,” she says, firm.

He stares at her for a moment longer, then drops his arms back to his sides. He stands up, starting to pace around the room. He kicks his toolbox, so lightly that Esme thinks at first that it’s an accident.

“If I don’t get the surgery,” he says, “then I’ll definitely have time to get everything done for you before . . . before I go.”

“I don’t want you to do things for me.” Her voice is rivaling Dr. Monotone’s. “I want you to stay here with me.”

His shoulders are tensed straight across like a tripwire. “What if I can’t, Esme? If I have more than a week, I can make sure you’ll be okay. I can set you up, get all our finances right, fix up the apartment, you know, I can take care of you!”

“You’ll survive the surgery,” she says. “And it will work. I know it.”

He’s not listening. He’s making a list in his head of everything he must do before he dies.

She pulls her keys out of her pocket, and from across the room, Davis stops, staring. He shakes his head. “For this?”

Esme smiles, a pale, empty imitation of the painted smile on her painted face framed behind her head. “Why not? Let’s see what fate has to say.”

He sighs. “Okay, fine. Ask it.” But he stays on the other side of the room.

She holds the little ball in both hands, the 8 facing up. She takes a deep breath. “Should Davis get the surgery?” She shakes it, three sharp spasms, then flips it over to see the answer.

“What does it say?” Davis’s voice is small, searching, and Esme thinks that maybe he will actually do whatever the ball tells him.

She looks at the little die pressed up against the clear window. Outlook not so good, it reads.

She swallows hard, raises her eyes to his, trying to keep her face smooth, trying to keep her fingers and voice from trembling. His eyes are pools of trust. “Without a doubt,” she says, holding his gaze.

Davis nods several times in succession. “Okay,” he says. “Okay. I’ll do it then.”

#

That night, Esme dreams of her grandmother. She was twenty-three when she married Esme’s grandfather and seventy-four when he died. It was like the whole time Esme had known her, she had had fireflies swarming beneath her skin, behind her teeth, between her toes. She glowed, she hummed. And when he died, so did they, the fireflies. Not all at once but one by one, dimming her in increments until she went dark.

The last time Esme saw her grandmother alive, she couldn’t stop talking about dying. It had been ten years since he died and she ached for him so hard Esme could almost see the magnetism drawing her life to a close. She told Esme she wished she’d died first. Then she told her that wasn’t true, not really, she didn’t want him to go through what she had gone through, but just why did she have to wait ten whole years to see him again?

In the dream, her grandmother is sitting alone at her kitchen table in the dark. Boxes of tissues and bottles of pills surround her, and piles of bills she can’t read. She can’t find her glasses.

When she turns to Esme she thinks she is her grandfather. “Bill?” she calls, and her voice is thread-thin in the darkness. “Is that you?”

Esme opens her mouth to call back to her, but nothing comes out. “I’m all alone,” her grandmother says, turning back to her table. This is what it looks like, when death tears love in half.

#

The surgery is scheduled for Friday morning. On Sunday, Davis is bedridden by a particularly violent migraine, and they agree that he should take it easy until the surgery, so he calls his boss and takes off the next couple of weeks.

On Monday, Esme has to go to work.

She would rather stay home and care for Davis, who’s still not feeling very well, but elementary school vice principals aren’t given the luxury of a lot of paid time off and she has to save it for next week.

So she spends the day in her colorful, windowless office where, one day, she will return for the first time after Davis is gone and she’ll re-teach herself to look at colors and write with a steady hand and speak to a child without passing grief along to them, hooked on the strands of her voice.

But she can’t think of all that now.

In the silence of her office, far from Davis’s eyes and ears and intruding tumor, she lets out a breath she’s been holding since the hospital. It rattles and ricochets off her ribs and her teeth and strings itself shakily out in front of her.

She’s surprised when she doesn’t cry.

Davis is being frustratingly selfless about this whole thing, maybe out of fear, but it makes her selfishness, her lie, stick out blood-red on the backdrop of their blissful relationship.

Esme suspects that right now, while he has their home to himself he, too, is letting out his breath, letting his grief spiral into the room with him. They had always been great at sharing love, happiness, light. They had never quite figured out how to share the hard stuff. Each of them always kept something just to themselves.

By the time the last bell rings, Esme is almost dreading going home.

When she turns into the hallway that contains their front door, at first she doesn’t know what she’s seeing.

A shape, crumpled between floor and wall. Familiar brown skin.

A flash of red.

Esme’s heart stops. She’s already lost him?

She has her phone out, the 9 already dialed before it registers in her mind that the red is just rose blossoms, their stems cupped in Davis’s hand, and he’s looking up at her, managing a faint smile.

Her chest is heaving as if she’d sprinted home. “What happened?” she asks, and a spike of anger textures her words.

Davis’s smile falters. “I wanted to get you flowers,” he says, his voice just slightly unsteady. “Got dizzy.”

Esme’s anger inflates in her ribcage. She keeps her mouth clamped shut and screams at him in the confines of her own head, listing everything that could have gone wrong, all the ways he could have accidentally left her. She reaches a hand down to pull him up, imagining him collapsing not in their hallway but in the middle of a crosswalk. She supports him through their doorway, imagining a car tire rolling obliviously over his skull. She helps him onto the couch, seeing his brain splattered across asphalt, tumor sticking out unnaturally white.

“You’re mad,” Davis observes.

“I’m not mad,” she says, forcing her voice even. She pulls a blanket over him. “Does your head hurt?”

“Es, I’m sorry. I just–I needed to do something.”

She goes to the kitchen, fills a glass with cold water, grabs his pain pills.

Davis reaches up, closes his fingers around her wrist. “I’m okay,” he says. “It’s okay. It’s just a migraine.”

Esme’s hands start to shake, the pills rattling. “You can’t take risks like that,” she says. “I’d risk anything to do something for you,” he says, without a moment’s hesitation.

Esme has to take a breath to keep her voice from rising, remembering his migraine. “You do everything for me,” she says. “Don’t you get it? I can’t live without you!”

She closes her eyes. She wishes the cancer was in her brain instead. She wishes it so hard she can almost feel it growing behind her eyes, biting into her occipital lobe. Leaving him and coming into her.

“I’m sorry,” Davis whispers. “I can’t live without you either.”

And she stops wishing. For just a moment, it was Davis sorting her laundry, him staring at Goodwill bags, him feeling her hand grow cold, and it doesn’t feel any better.

She pulls the lid off the pill bottle, struggles with shaking fingers to pull out two pills, sets them in Davis’s palm. His own uncoordinated fingers send water dripping down his chin.

She wipes it off with her shirt. This could be the rest of his life. Cleaning him, feeding him, caring for him. Her Davis could already be gone.

“You should get some rest,” she says. “You’re upset,” he says.

“I’ll get over it,” she says, a little too much force behind the words. “Please rest.” Davis nods. His eyes close.

Esme walks to the bedroom, slow. Heel. Toe.

As soon as she closes the door behind her, her breath starts sawing through her chest, fast and hard and scared. Her hands come up to the roots of her hair and she grips, not pulling just holding, holding herself in when all she wants is to spill onto the carpet, seep into the fibers, a stain that will never come out.

She kicks her foot out. A row of books tumble off her lowest bookshelf, paper folding and crunching in the cascade.

She kicks again. An explosion of pain in her big toe as it strikes the painted wood of the shelf. She remembers how Davis just had to come fix this shelf, to leave her with this picture perfect life, everything in its place except for him. If Davis is leaving, everything is going with him.

She kicks again.

Again.

The wood splinters away from the wall, a chunk of plaster raining dust on the pile of books.

“Come and fix it, Davis,” she whispers with the force of a scream.

If she tears the shelves off the wall every morning, maybe then he’ll stay.

She grabs the hanging shelf, rips the other support away from the wall. The wood grain is rough in her hands. A splinter buries itself in her thumb.

She throws the whole shelf across the room. It hits Davis’s photo wall, sends a collection of polaroids fluttering to the ground.

Esme’s chest heaves. She waits for Davis to come stumbling in, ask what the hell she’s doing, start cleaning, start fixing. He doesn’t. Maybe he’s asleep. Maybe he’s afraid of her.

Maybe he just doesn’t care anymore.

Why should he? She lied to him, for the chance that she could put off being alone for a few years. If it wasn’t for her, he could die in peace.

He should hate her.

She pulls the Magic 8 Ball keychain out of her pocket. Why couldn’t it have just said yes to the surgery?

Her breath catches in her throat. “Am I doing the right thing?” she asks, shaking the ball.

My reply is no.

“Am I doing the right thing?”

It is doubtful.

She falls to her knees, jerking the ball, breath coming in gasps. “Am I doing the right thing!”

My reply is no.

#

At their wedding, Esme and Davis did not say “Til death do us part.” They did not plan to die, and if they did, they did not plan to part. They tried to think of something else to say in its place, but everything they came up with sounded cheesy and fake, so they just cut it out.

As she sits in the waiting room on Friday, Esme thinks about parting. To her, the afterlife doesn’t really exist, not in the heaven-and-hell biblical sense. But when they’re both dead, she knows they’ll be together, somehow. Maybe death will be like dreaming a good dream, inventing a world for your mind to live in. And hers, of course, will have Davis.

Before he got wheeled away to surgery, he tried to say goodbye. She didn’t let him. She wasn’t ready to say goodbye today, and she told him so, told him he better not think of leaving her.

His eyes were that deep well again, and he told her he loved her and he would do everything he could to live. “I don’t want to see you die,” he said. “But I’d like to see the rest of your life.”

“I lied,” she’d blurted out. It had burned its way out of her throat. “About the Magic 8 Ball. It said no to the surgery.”

Davis had smiled, a real smile, like the one he wore on their wedding day. “I know,” he’d said.

And then they took him, down the hall, her “I love you” still in his ears, and she was left in the waiting room.

Mostly, she watches the clock. It’s monotony, like the doctor’s voice, and she is beginning to understand the merit. But her mind strays. First, she runs desperately away from the possibility that her life without Davis will start today.

She imagines a tornado sweeping through this hospital, picking up Davis from his operating room and then coming to pick up her from this waiting room and swirl them together in its funnel cloud until they collide, and they are both killed on impact with each other, pushed together with such force that when the first responders pick them out of the rubble they cannot separate the bodies and they have to be buried in a single coffin, together.

Then comes hope.

She imagines that Davis’s surgery is successful. He comes home and he gets radiation and he recovers. They learn the word remission. In a couple of years, Esme misses a period and nine months later they have a baby girl. He coaches her soccer team and gives her a car he fixed up for her when she graduates high school. They have three grandchildren and they see them all enroll in college. When they retire, they adopt a senior black lab and spend their days quietly.

They die on the same night in the same bed, one heart sensing when the other has failed and quickly following suit.

Esme sits in the waiting room and she knows that neither of these things will happen. She knows that Davis is dying and she is not, and sooner or later she will have to learn how to say goodbye.

She pulls the Magic 8 Ball keychain from her purse, and stares at its scratched surface. She wonders what would have happened if it had said no to dinner with Davis all those years ago, if she would hurt more or less having never known him.

“Will I be okay?” she asks, and she shakes the ball.