Porter House Reads: The Best Writing We’ve Read This Summer

Why do editors edit? The answer, I think, is a somewhat desperate ploy to elevate our time spent reading from that of a hobby to a job. Even if that job fails to offer up even a single paycheck—as editing so very often does—it’s a way to trick our brains into believing we can be productive even while we’re pursuing the activities we most love. We here at Porter House Review have elected to spend most of our free time reading, discussing, and championing the literature that populates our Submittable queues, and when that well runs empty, we turn to books and other literary journals to get our fixes. In our new Porter House Reads series, we hope to exploit even that bit of leisure in order to have more conversations with you, the reader, about which words have most recently animated the fleeting jolt of collective aliveness that only the best writing can gift us.

Taylor Kirby, Asst. Managing Editor

Orange World by Karen Russell

Orange World by Karen Russell

In her most recent collection, Russell captures her characters in movements that seem always to arc back toward love. These short stories possess Russell’s signature strangeness, remaining at the same time as wise as they are wondrous. From close friends attempting to burgle the lodge of tenants who may not be living to a new mother trying to unlatch the hold of a neighborhood demon, Orange World makes strange the workings of the everyday, so that we can more readily inquire into what animates our lives.

Kaitlyn Burd, Fiction Editor

Just Kids by Patti Smith

The godmother of punk rock’s National Book Award-winning memoir might be my desert island book. I call it the first pop-up book I’ve read that does the job with words alone. The story of her relationship and friendship with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe as struggling artists in New York City is harrowing and hilarious. Smith’s language is ethereal and often lyrical, well juxtaposed with the troublesome, tangled, frayed nature of the tale. Read this with hot coffee, then microwave the mug after you forget it’s there.

Ben McCormick, Nonfiction Editor

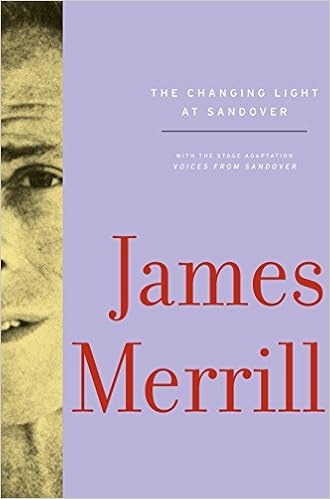

The Changing Light at Sandover by James Merrill

The Changing Light at Sandover by James Merrill

Merrill’s epic is in large part a rearrangement of transcriptions of ouija board sessions in which he and his partner, David Jackson, claim to have communed with the dead, from W.H. Auden to W.B. Yeats. The poet simultaneously plays the hermeneut and the critic, questioning the spirits when they are vague (or sometimes intentionally obstructive) and anticipating both the difficulties and the joys that a reader might encounter in the work. Stunning music from beginning to end.

Asa Johnson, Poetry Editor

Because They Wanted To by Mary Gaitskill

Because They Wanted To by Mary Gaitskill

Because They Wanted To is full of subversive sadness and adult angst, from the story “Tiny, Smiling Daddy,” in which a woman publishes an article about her father without his knowledge, to the title story, an exploration of abandonment with a haunting ending. Gaitskill writes with a quirky lyricism about emotional dysfunction, families, lovers—even dentists. “The Wrong Thing,” a novella written in four parts about a teacher’s foibles in sex and love, closes the book and leaves you to wonder what your own darkest thoughts would tell the world about you if they found their way onto Gaitskill’s pages.

Natalie Brown, Reviews Editor

Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

In this collection of essays, Sedaris wittingly weaves together wacky stories of his childhood with poignant reflection upon how many of his early situations shaped his privilege. From school speech therapy to American cultural critique to guitar lessons gone wrong, Sedaris’s work reads like a stand-up routine, a private show incapable of being put down.

Emily Ellison, Interviews Editor

“Color and Light” by Sally Rooney

“Color and Light” by Sally Rooney

I love anything by Sally Rooney (including the beloved Normal People), but “Color and Light,” her recent New Yorker story, really blew me out of the water. Rooney’s ability to engage with a complicated and political power dynamic, and resolve that dynamic in a deeply and authentically ethical way, AND write those impeccable goddamn sentences—what a triumph.

Ali Riegel, Copy Editor

The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human by Jonathan Gottschall

The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human by Jonathan Gottschall

“Tens of thousands of years ago, when the human mind was young our numbers were few, we were telling one another stories. And now, tens of thousands of years later, most of us still hew strongly to myths about the origins of things . . . We are, as a species, addicted to story. Even when the body goes to sleep, the mind stays up all night, telling itself stories.”

Gottschall attempts to explain, by using biology, psychology, and neuroscience, why we as humans are so enamored with stories. Though he uses science to explain human behavior, the writing in this book is anything but pedantic. If you’ve ever wondered why you can’t stop binge-watching your favorite Netflix show, then you need to read this book.

Rachel Spies, Podcast Editor

Woman on the Edge of Time by Marge Piercy

Woman on the Edge of Time by Marge Piercy

Fictional dystopias are increasingly popular, but what about fictional utopias? For better or worse, you can travel both backward and forward in time with the underappreciated classic Woman on the Edge of Time by Marge Piercy. Published in 1985, WOTEOT’s recipe—one part sci-fi, one part political critique, one part psychological horror, one part feminist revenge fantasy—still feels decades ahead of its time. In WOTEOT, Connie, a middle-aged Latina from Brooklyn, is involuntarily committed to a mental institution by her niece’s pimp, but is she really crazy, or is she in fact time traveling to a utopia in the year 2137? Although literary in style, WOTEOT is an action-packed masterwork that deserves to be widely read, perhaps now more than ever.

Emily Cordo, Business Manager

Corregidora by Gayl Jones

Corregidora by Gayl Jones

Legend has it that after Toni Morrison, then an editor at Random House, read Gayl Jones’s Corregidora manuscript, she said “that no novel about any black woman could ever be the same after this.” Indeed, this sparse, fragmented postmodernist masterwork is a stunning testament to how traumatic legacy is generationally inherited and experienced in real time. When Ursa, the novel’s protagonist, has an emergency hysterectomy after a physical confrontation with her husband, she loses the ability to orally and genealogically pass on her family history. Despite the insistence of Ursa’s Great-Gram and Gram—who were both enslaved and raped by a Portuguese plantation owner living in late nineteenth-century Brazil—that Ursa “make generations” in order to “hold up” slavery’s violations, Ursa can no longer serve as her foremothers’ substitute. Now Ursa must construct an identity apart from “generation-making,” a task fraught with physical and psychological anguish. The novel that follows is a narrative lighting strike, a tender and painful ode to survivors of ancestral trauma.

Brady Brickner-Wood, Managing Editor

The King is Always Above the People by Daniel Alarcon

The King is Always Above the People by Daniel Alarcon

This story collection will surprise and reward its reader for investing in the lives of the very real people who populate its pages. One person’s story is the story of a “thousand” people, but such tales are not to be generalized. Rather, each story is here to remind us of the ever-increasing complexity of human nature as it pertains to family lineage; to the trials faced by generations new and old; to immigration and the splitting of identity upon the crossing of borders; as well as to the power and confusion behind possessing an education.

Will Pellett, Content Editor