From the Front Porch Archive: A Good Laugh

Yves Klein “Leaping into the Void” (1960)

Front Porch Journal published its final issue in Spring 2018, after serving as the literary review of the Texas State MFA Program for over a decade. In celebration of Front Porch, we present “From the Front Porch Archive,” a series intended to showcase the phenomenal work published by our predecessor. Every so often, our editors will share stories, poems, and essays from Front Porch that captivated us then, and continue to do so now. We hope you enjoy.

A Good Laugh

Judging by the grandeur of the hotel, which loomed like a giant lighted obelisk over Portsmouth’s downtown waterfront, I expected the convention to be attended by masses of businesspeople dressed in sharp suits and blouses, throwing back martinis with an air of self-indulgent abandon—talking of investment portfolios, the headache of finding the right private school for their kids.

Most of the places I had performed—college pubs and semi-fancy restaurants looking to bring in a little extra bar revenue—tended to cater to Richmond’s legions of privileged art school students, whose nose rings and shabby thrift store clothes spoke less of a life of hardship than it did a scathing hatred for their parents. All that mattered was that they came to the shows determined to laugh, which they did more often than not. Given this, I had every reason to believe my performance tonight would be a success.

So I was stunned to see the cavernous lobby teeming with paunchy figures in t-shirts and cutoffs, yammering in thick southern drawls as they tried to make sense of their printed convention schedules. Juxtaposed with the hotel’s sterling red carpets and brass wall sconces, this crowd didn’t resemble convention-goers so much as a massive assembly of Grand Canyon tourists.

I had been tapped as a feature performer by a fellow comic named Odyssey Michaels (his real name is Michael Jackson, and so for obvious reasons he’d adopted a stage name). As is often the case in the comedy trade, I knew almost nothing about the gig other than what he’d told me over the phone two weeks earlier. That I didn’t even feel it necessary to at least Google the gig was a testament to both my trust in Odyssey as well as the swell of confidence that his offer had brought on.

“Who’s hosting the convention?” I’d asked.

“Hell if I know,” Odyssey replied. “But it’s like five hundred people, two hundred bucks for a twenty-minute set. You interested?”

Of course I was. At this point, I had been performing recreationally for just over four years and had enjoyed some minor success. Lately, however, I’d been toying with the idea of taking it to the next level, booking a few tour dates, maybe, giving an honest shot at going pro. What did I have to lose? I was in college, with my only other responsibility being the couple nights a week I waited tables at a failing restaurant franchise. There was nothing in my life that couldn’t be shirked in favor of a chance of stardom. That, at least, was how I had interpreted Odyssey’s offer, as the first big step on the path to fame.

There were four of us on the ticket: me; Odyssey; Mike LaPara, with whom I’d performed a handful of times at other clubs; and Laughing Lenny, the show’s headliner, a veteran of HBO and BET. I was the first one to arrive, having overestimated the traffic between Richmond and Portsmouth. With two hours until show time, I wandered into the bar to have a drink and go over my set list. The place was small and dimly lit, the clunky wooden tables and chairs clustered cozily together on the three-tiered floor. Despite being packed full of people, no one appeared to be drinking. Not alcohol, anyway. Most of them were nursing glasses of water or bottles of orange juice. Every last one of them had a cigarette smoldering between their fingers.

The bartender brought me my beer, and as I sifted through my wallet, the woman on the barstool next to me leaned over and exclaimed, “Oh, I know you must be in recovery.”

“Excuse me?”

She gestured to the clump of bills in my wallet, accrued from a double shift I’d worked the previous day in exchange for having tonight off. She was short with red chrome highlights in her hair and the rangy frame of a marionette. “Look at all that!” she said, smoke wafting from her jagged maw.

“Look how much you’re saving now! More money than you know what to do with, am I right?”

I glanced back and forth between her and the bills. “I’m not sure what you mean. You want me to buy you a drink? Is that what you’re asking?”

“What? No, I don’t want a fucking drink!” Her bony face twisted into a sneer, as if I had just vomited in her lap. “I’m sober, thank you very much. Can afford my own damn drink anyway. The fuck is the matter with you?

“Honestly, I don’t know,” I chuckled, struggling for some expression of affability, but it all felt wrong somehow. “I’m one of the comics? We’re doing a show? At eight? They didn’t tell us much. What kind of convention is this?”

The woman rolled her eyes and then took a drag of her cigarette. She swiveled around her barstool to face the other way. Before turning her back on me completely, she muttered, “Narcotics Anonymous.”

* * *

Here’s what I loved about doing stand-up: you stand on a stage and get to say things that, under ordinary circumstances, would cost you friendships, your job, or even a few teeth. In fact, you don’t just get to say these things; you’re supposed to. That’s why people go to comedy shows—to hear things about the world that can only be said in that particular context. If the late comic Richard Jeni is to be believed, comics are the only people on earth with license to tell the absolute truth. And at the time of my doomed performance at the Renaissance Hotel, I wanted to believe that this was what I was doing, spreading the absolute truth, if only because of how noble and beyond reproach it sounded. It made it seem as though cracking jokes was a form of philanthropy.

Except, maybe license isn’t the right word—responsibility might be more accurate, comedians have a responsibility to tell the truth. After all, a joke is only funny insomuch as it offers some insight about the world. And to this end, things like timing, intonation, body language, facial expressions, and clarity of speech take on such significance on the comedy club stage, because they are central to your delivery of that truth. Knowing this, I had spent the past several weeks honing my set, mentally mapping each pause in delivery, every facial tic. But the sober woman had unnerved me. What did I, sheltered suburbanite that I was, know about the lives of recovering drug addicts? All at once, the very notion of telling jokes seemed vulgar and cruel, like magic tricks at a funeral. I wasn’t an addict of any sort, could hardly stand more than a few drinks in a sitting. I had no frame of reference for what these folks had been through, which made the notion of telling jokes seem all at once vulgar and tasteless, on par with performing magic tricks at a funeral. A gathering of recovering substance abusers wasn’t a place for comedy; it was a place for somber and possibly painful self-reflection, where strangers grappled with their collective failures. It was not a place for revelry.

The other comics arrived. Odyssey was in his early thirties, small in stature with the kind, wholesome demeanor of a kids’ show host. Mike was stocky and broad-shouldered, with stylishly unshaved jowls; save for a handful of other folks in the bar, he and I were the only white people present. And Laughing Lenny, whom I was meeting for the first time, had a freshly shaven head and the loud, florid swagger of a revivalist preacher.

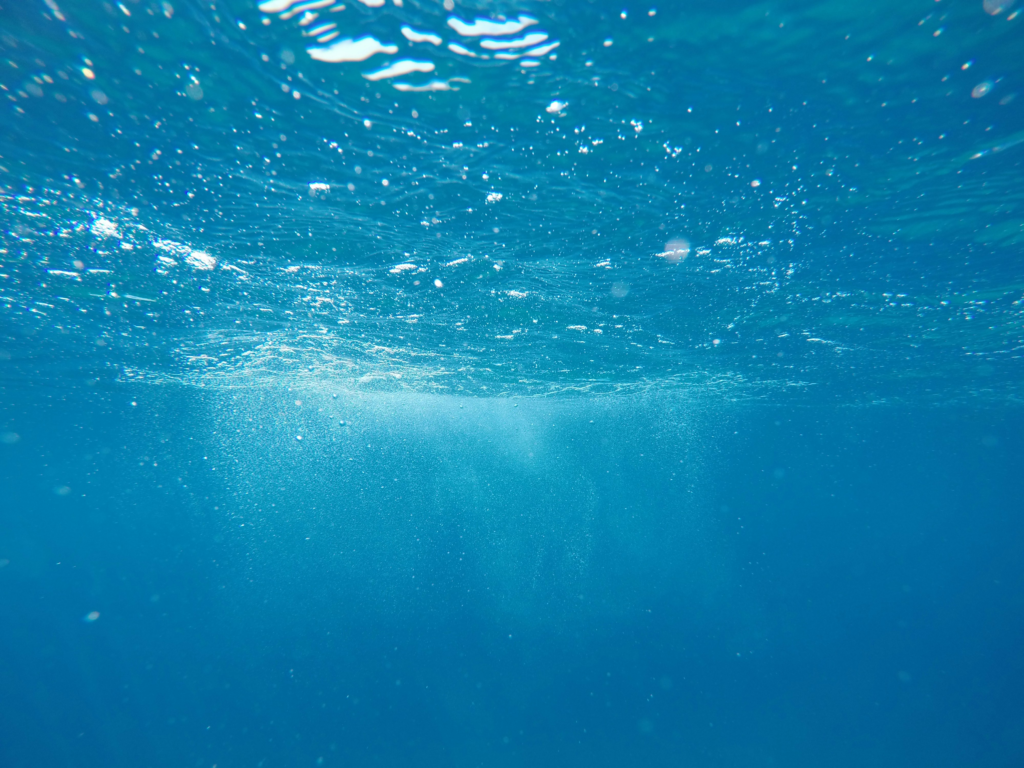

They each ordered a drink, and the four of us migrated out onto the ballroom balcony. We stood by the railing, sipping our beers, enjoying the tepid August breeze. Below us the inlet glimmered in the light of high-end waterfront restaurants. The three men talked idly about shows they’d done recently, performers they’d worked with. It was like listening to a bunch of retired soldiers swap war stories, the sense of hard-won camaraderie. Yet, as I—the novice—stood back and listened, smiling and laughing when prompted, I couldn’t shake my anxiety over the show. It was more than just stage fright; I felt like I had made some enormous mistake but didn’t yet know the consequences.

My discomfort must have been obvious, too, because after a couple minutes Mike sidled up to me and said, “Holding up okay?”

“Yeah, more or less.”

“Relax. You’ll do fine. You’re a funny guy.” He sipped his beer casually. Mike was one of these comics whose onstage persona was the exact opposite of his actual persona. When he performed, he was bombastic, animated, delightfully foul-mouthed. But in his day-to-day life, he was soft-spoken, almost disarmingly so. This was something I was still getting used to: no one is ever themselves on stage. Your character is a streamlined version of you, spearheaded by a temporarily amplified ego—not unlike a first date. After so many years working the East Coast circuit, my cohort had long established their characters and could switch in and out of them fluidly. But the fact that I was still learning about mine only drove home the growing suspicion that I was dangerously out of place here.

“I’m just not sure what’s appropriate,” I said. “What do ex-junkies find funny?”

Mike shot me a look similar to the one the woman in the bar had given me. “Same stuff everyone finds funny, I guess. They’re just people like you and me. They’re here for a good laugh, you know?”

* * *

At a quarter to eight the four of us strutted into the ballroom. It was massive, the cream-colored walls adorned with ornate gold sconces and a long balustrade. Crystal chandeliers the size of hot tubs hung above the rows of blue padded chairs, which were now beginning to fill up with people. I was still making edits to the set list I’d spent the past two weeks crafting, swapping out some of the edgier jokes for safer material, when Odyssey strode up to the stage to get the show started.

“How you doin, Portsmouth?” he cawed into the microphone.

After the crowd’s obligatory round of applause, he said, “I bet ya’ll wish you were fucked up right about now, huh?”

At this a chorus of cheers blasted through the ballroom like that of sports fanatics whose team just pulled off a last-minute victory.

For five minutes or so, he patrolled the stage with an air of casual authority, firing off jokes in finely-tuned rhythm, each punchline eliciting bursts of laughter. He had a breezy, thoughtful way about him, as though he could just as easily have been performing for a crowd of five instead of five-hundred: “Yeah, everybody likes to get fucked up for a show. Concerts, comedy shows, whatever. Makes it easier to just shut up and listen. Shit, why you think they serve wine in church? You give me a couple drinks and I’ll believe whatever you say, Mr. Preacher-man!”

Once the crowd was adequately primed, Odyssey introduced Mike, whose ten-minute set consisted largely of raunchy one-liners: “I got four kids from three different women. People are always like, ‘Yo, that makes you half black!’” He grabbed the crotch of his oversized jeans. “Yeah, but not the good half!”

The audience continued to howl, arms and hands flailing in joyful gesticulation.

“But hey, still makes me blacker than Tiger Woods, am I right?”

For an instant I tensed up in my seat, anxious to see how the joke would land. The howling rose to a jubilant roar. A trio of women a few rows from the stage stood and clapped exultantly. An obese bald man wiped tears from his eyes.

By the time Mike finished his set, I had started to relax. The jokes so far had been obvious. Dull and pandering. Yet, the clamor of the crowd assured me that they were determined to laugh, just like Mike had said. All I had to do, I told myself as Odyssey welcomed me to the stage with a brotherly slap on the back and then handed me the mic, was keep that enthusiasm going for twenty minutes.

“How’re we feeling tonight, guys?” I called out.

There was a respectful round of cheers, not quite as intense as I’d hoped, but I was just getting started.

While revising my set, I had decided to open with some lighter material about the tropical storm that had pummeled the Eastern seaboard only weeks earlier: “Boy, I tell you, this weather is crazy, isn’t it? I don’t mind snowstorms, and I don’t mind heat waves, but not in the same day, am I right folks?”

A smattering of chuckles.

“And then you’ve got all these people running to the stores for supplies like it’s the end of the world. I saw a woman with a shopping cart full of bags of ice, and I’m like, ‘Jeez lady, are you transporting organs or building an igloo?’”

From somewhere down front I heard what sounded like a groan; I chose to interpret this as ironic approval. They were anxious for me to get to the edgier stuff, the dicey jabs about drugs and race and sex that Odyssey and Mike had doled out like fast food. But I wasn’t about to take that chance, too much room for misinterpretation. I was better than that.

Instead, I started into my next bit, a pointedly nonthreatening political quip—“We’ve got Schwarzenegger in California, you had Jesse Ventura in Minnesota, why don’t we put the rest of the Predator cast in office?”—but that was when the booing began. Just a handful of folks near the back at first, but within seconds it had spread throughout the entire room. A few people were gesturing theatrically for me to get off the stage.

I stammered, losing my place in the bit. I could feel my face growing red with heat. My voice cracked as if I’d plummeted back into awkward adolescence. A couple near the aisle stood, locked hands, and stalked out of the ballroom. Another followed. Then whole clusters of people, men and women who, despite having paid fifteen dollars a ticket, were now inclined to skip the second half of the show after I had taken what I’d believed to be the high road.

As the get-off-the-stage gesturing grew more emphatic and entire rows of people began shuffling out into the lobby, shaking their heads like witnesses to a grisly car accident, I spotted Odyssey, seated in the back corner of the room, making a slashing motion across his throat: It’s over.

“Okay well, thanks guys,” I spluttered. “You’ve been great.” Then I slumped off the stage, dizzy with humiliation, having made it through less than five minutes of my twenty-minute set.

* * *

Amazingly, no one has ever been able to offer a definitive answer to the question of what it means for something to be “funny.” Like any universal experience, humor seems immune to definition, frustratingly so, although that hasn’t stopped scholars and artists alike from looking for an answer. Theories abound, many of them derived from Freud’s examination of tendentious humor (jokes made at someone else’s expense) and non-tendentious humor (jokes whose effect is dependent upon rhetoric and not a “victim”). One of the more popular is the misattribution theory, published in 1980 by media scholars Jennings Bryant and Dolf Zillman. This theory, which focuses on tendentious humor, holds that what we think we are laughing at in regard to these sorts of jokes and what we are actually laughing at are in fact very different. Tendentious jokes, which tend to be comics’ sole medium, allow us to mock others without consciously acknowledging that we are doing so. For example, scholar Magda Romanska points out that royal court jesters traditionally came from marginal positions in society and often suffered from physical deformities (as in the case of Triboulet, the real life basis for Verdi’s Rigoletto, who suffered from microcephaly) as well as mental disabilities like autism and Down’s syndrome. However, it was because of their nonthreatening status that they were permitted to openly ridicule the king. While the jokes were ostensibly at the king’s expense, guests were, to some degree, actually lampooning the jester himself. In other words, the jokes were at the king’s expense only because they were at the jester’s expense.

It’s ironic then, that while the jester came to be seen as a source of fundamental truth and wisdom within the royal court, it was this very perception that precluded his freedom: as Romanska points out, the jester was a slave for life and could only be freed by royal decree. Indeed, humor always comes at cost. It is a response to events or conditions we find unacceptable, sometimes even unbearable, and there is a darkness to it that, while well-documented, often escapes us in the moment. Comedy, however, offers us a space to confront that darkness, to come away with a better understanding of where we fit into the world, how we find meaning in our lives, how we are supposed to navigate our differences—questions that are sometimes too weighty for us to address directly. These, I suspect, are the sorts of truths to which Richard Jeni was referring. And the comedians who understand this tend to be fairly successful (by comedians’ standards, anyway). But there are plenty who, like me in that hotel ballroom, fail to recognize what the audience is really looking for, simply because we can’t reconcile their desire to laugh with the reality of how unfunny those truths are in reality (to this end, it’s worth pointing out that Jeni committed suicide in 2007 after a lengthy struggle with clinical depression).

And so I suppose that’s why we laugh, because what other choice do we have? The world would tear us to pieces otherwise. We laugh because it’s the best defense we have. We do it because it’s only a few perilous steps away from hysteria.

* * *

From the back of the ballroom, I watched sulkily as Laughing Lenny worked the crowd—the remaining half—like an evangelist at a revival. After a couple moments, Odyssey sat down beside me. He gave my shoulder a friendly shake. “You okay?”

I nodded. “I just don’t know what happened up there.”

“I think it’s just a cultural gap,” he said, lacing his fingers thoughtfully behind his head. “You’re coming at them from a completely different world.”

But his assurance was of little comfort. I wanted to believe that the audience had judged me unfairly. And maybe they had a little, but that wasn’t why I had been booed off-stage. The fact is that in my attempts to sanitize my set, I hadn’t made any efforts to bridge that gap. Instead, I’d pretended like it wasn’t even there. Under ordinary circumstances that might not have been as much of a blunder, but ordinary circumstances don’t demand the kind of honesty that the audience was expecting. In fact, it wasn’t until much later—years actually, after I’d resigned myself to the fact that I wasn’t thick-skinned enough for comedy and opted instead for the far less colorful life of an academic—that I would come to understand the truth: I hadn’t lied to them outright, but I hadn’t been truthful either.

At that moment, however, I was too angry to appreciate any of this. All I wanted was to be anyplace else, far away from the Renaissance hotel and the vengeful crowd. I’d only hung around because leaving in the middle of Lenny’s set would have been disrespectful.

Odyssey reached inside his blazer and produced my check. Two hundred dollars for five minutes of stage time. Somehow, this only seemed to make things worse.

I thanked him and tucked it in my jacket pocket. “Would it be really rude if I went ahead and took off?” I said.

He held my gaze for a second, a knowing little smirk playing at the corners of his mouth. “Man, if I were you, I’d have already been gone.”

* * *

I plodded down the hotel corridor, through the red-carpeted lobby, toward the parking deck, pretending not to recognize the bevy of smokers hanging around outside the automated hotel doors; a few of them had been among the throng that had fled during my set.

Outside, the air had grown windy and frigid. Fog hung over the water in thick, gauzy strips. My footfalls echoed glumly as I trudged up the ramp of the parking deck. As I was rounding the corner to the second level, a white hatchback swung into a space up ahead of me, muffler coughing, and out climbed an older man in a yellow flowered shirt and jean shorts. He gave an effortful grunt that resounded throughout the structure as he came to his feet. His face, I saw as he got closer to me, had the same timeworn character as all the other convention-goers. “See you next year, man,” he said as he passed, mistaking me for a fellow addict in recovery.

And for just an instant I felt compelled to set him straight. No, I wanted to tell him, you won’t. I’m just a tourist, an interloper. I don’t belong here. But instead I summoned a smile and, without thinking, replied, “See you.”