Good Women

Andie

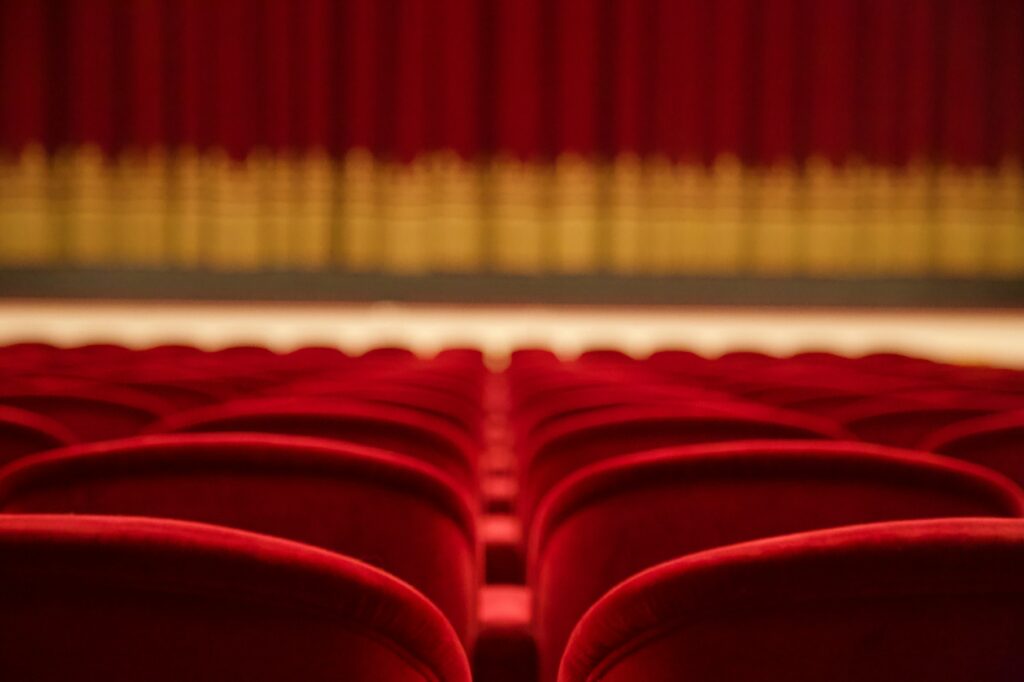

We had the same opening night and I know she planned it that way. The front page of The Santa Fe Cultural sat on the counter at the gas station and screamed at me: “Sienna Wu-Cryer’s highly anticipated play Good Toys premieres tonight at the Downtown Center for Performing Arts.” So I skipped my premiere and went to hers. I heard them shouting, “Where’s Andie?” as I left the theater. “Andie, come back.” “Andie, it’s a one-woman show.” What they didn’t understand was, how could I possibly?

There was a line out the door at the Downtown Center. A poster for Good Toys was framed with a border of yellow bulbs and featured a small blonde boy holding what looked like a chicken bone. I surveyed the people in line, hoping to see whatever it was about them that led them here tonight, specifically here, instead of anywhere else in the world they might have gone. Young, all of them. What I felt was gratitude that they had not come to my play because they would not have understood it.

I’m at Rocky’s house by the railyard now, thinking of Sienna, remembering when I once thought what might fix me was an agreeable man, one willing to do my bidding. An agreeable, patient man. I’m thinking of agreeable men because Rocky has begun to date Pete, a man who works at the brewery next door. Rocky and I sit together in the living room while Pete tinkers in her kitchen with ground beef and a frying pan. Pete is short and extremely agreeable with a face like a Depression-era bank robber.

My father is one of them, too, the agreeable men. Fifteen years ago, Sienna Wu married my father and became Wu-Cryer, and that’s the only proven reason I have to know her. I was thirty-eight and Sienna was thirty, and my father was twenty-five when I was born. But this is all too much math for this time of night.

“Is your play good?” Rocky asks me suddenly. Rocky has been my friend since second grade, when my father moved us here, to Santa Fe. She lets me smoke inside, and she has tattoos under her eyes and on her fingers and all over her neck and arms.

“Most plays are bad,” I tell her.

“That’s not true,” Pete says, coming into the room with three bowls and three forks. White rice topped with ground beef with a squirt of barbeque sauce. I want to retch.

“Then why do you do it?” Rocky asks me.

“Why does the songbird sing? Why does the tax accountant tax account?”

“La Cage aux Folles is good,” Pete says, settling into a corduroy recliner that I remember from years ago, when Rocky and I hauled it out of the Goodwill and into her truck.

“It doesn’t make you deep to be the barkeep who’s into gay musicals,” I tell Pete. Juxtaposition isn’t always interesting, but he doesn’t seem to know that. Sometimes his character can be sloppy, hastily written, a cheap bundle of clichés. I turn back to Rocky. “Because I have to. Because it’s all I know how to do and it’s all I’m good at.”

“Andie, you were really good with the horses,” Rocky replies. “Back then.”

“That’s just backstory,” I say to her.

“So, what’s her play about?” Rocky asks. “The child bride.”

Pete, holding his phone, reads out loud, “Sienna Wu-Cryer’s highly anticipated play Good Toys is set in an ambiguous present day and is about—” (I mouth along) “—a family of children making sense together of an unspeakable tragedy.”

“It’s easy to make art that’s about nowadays,” I say.

“And what’s your play about?” Rocky asks, something stupid in her voice. “Then-adays?”

I’m immediately annoyed at Rocky, at her forgetfulness, at her selfish insularity to not remember what my play is about. We have certainly spoken about this. I hate being here sometimes, with Rocky and Pete, a third arm of their unremarkable relationship. I simmer into my food as Pete starts to read a different article. The food is infuriating because it is exactly perfect.

“Andrea Cryer is set to premiere her one woman show, The Woman Destroyed,” Pete reads. “On Friday, in Gallery B of the Contemporary Arts House. A word-for-word adaptation of Simone de Beauvoir’s—” (he pronounces it dee-buh-vore, like herbivore) “—classic novel, The Woman Destroyed, Cryer’s work is an avant garde representation of the late-in-life decay of desire.”

“Word-for-word?” Rocky repeats.

“That means she plagiarized,” Pete laughs.

“I really do hate him,” I tell Rocky.

“You’re too old to hate so much,” she replies.

“I’ll buy some turquoise and curse him,” I say. Mom, that’s racist, Bodie says to me often. Bodie is short for Bailey, but she couldn’t say Bailey when she was a kid. Bodie is my youngest and, I suppose, my only. She is in love with Sienna’s neighbor, a boy who got a diploma the same year as Bodie from the Santa Fe Community College. These are the details that I monitor from time to time, the details I can’t find on the cover of the Santa Fe Cultural.

Pete does the dishes, then he and Rocky retire to the bedroom. I lie on Rocky’s couch and listen to them writhe and wail. She’s given me a cotton blanket with a wolf on it and left the TV playing for me like an unattended dog, but I cannot drown out their sounds, so I shut my eyes and recite my play to myself, from the beginning, refusing to fall asleep until I make it to the end, refusing to give way to the kinds of thoughts that only come out at night. I hear Rocky snore near the end of Act I. I stay motionless, only reciting the lines, refusing to know what I always know when the curtain closes: that I miss Rocky and the things we once were, that I miss her even when she’s right next door.

Sienna

She came by our home, again, your Andie. She left a note on the door, and by the time I saw her from our window and made it downstairs, she was gone. I know she misses you, even if she did not make it to the hospital to see you. The note, as always, was incomprehensible:

Bury your heart inside of bingo

I put it away with the others, in your desk that I will never clean out in case you come back to finish your work. Today is a day like many. I wake, I cry, I remain. In our bed, I have not changed your pillowcase. It stays there, waiting for you to rest your head. Every day you are not there, I worry you are not at rest. This thought is unbearable, an image of you unsettled and alone. It’s a play about unbearable thoughts, of husbands forever roaming homes, looking for daughters who never come back.

I feed our beautiful dog because I still do what it takes to get to midnight and morning and midday and Monday and all the next after that, again and again. The visits from Andie, however unusual, they help both of us, I think.

It’s a play about Andie, about us. It’s a play about two women who could have been friends, who still could be if we make it out of this, all of this grief, all of her disbelief that I might have loved you as deeply as I did. The Earth rattles for Andie. It’s a play about her footsteps, about the space she takes up, about how I was always jealous of that, about how badly I wished she would share it with me.

You would have been so proud of her. She finally did it. Her name on all the posters, a real production. I don’t know why she premiered it the same day as mine. But it didn’t matter, I had a ticket to hers, I was going to skip Night One of my show. You know how I am. How I do not like to see a thought go unfinished and how final it is to premiere. How final it would be to put away your glasses that are still in the living room, and how maddeningly unfinished our life together might always feel.

Bailey visits a lot. She is keeping Sunday Dinner alive. She loves it here, in our home. She always uses your favorite mugs, sits in your favorite chairs. She has been seeing Michael, you remember? Our old neighbor’s son. They are sweet together—Bailey with her mother’s thick, curly red hair, her eyes the color of pickles, and Michael with his long, straight black hair, his eyes like a campfire.

Tonight, Bailey takes your seat at the dining table, she serves everyone’s plates like you used to, she pours everyone’s wine like you used to. Bailey and Michael have helped me make your favorite meal, chicken piccata with an arugula salad, and even though no one likes arugula but you, we are eating it all. A play about eating it all.

“Sometimes I forget I’m related to her,” Bailey says.

“Don’t say that.” I tsk at her. “Everyone has challenges with their mother.”

“But you know.”

“I know,” I say.

“I hate going places with her,” Bailey goes on. “You never know who she’s going to insult. I wish she’d stayed in bed.”

“Hey,” Michael says. He puts a hand on Bailey’s back. “It’s okay.”

“I’m glad she didn’t,” I say. “I’m so proud of her play.”

“I can’t believe you got a ticket,” Bailey says. “And then she didn’t even do it. Not even because of Grandpa, she just didn’t go. Now they’ve canceled the full run, because Classic Andie.”

“Well, if she had done it, I wouldn’t have made it to the hospital,” I reply. “Because of Do Not Disturb. So, maybe, I’m grateful.”

“She doesn’t deserve all that,” Bailey says.

The truth is that, yes she does, because of your daughter, because of all that, because of everyone does, because of hopefulness, because of maybe, because of someday Bailey will miss her mother and someone has to keep tabs, because of hatred being too easy to swallow until it’s all you can swallow, because of fear that loathing might be an inherited trait.

Bailey was 8 when I met her, when she brought home a tiny skateboard a boy classmate gave to her with an inscription on the back: I love you —Eric. I gave her a Sharpie from the kitchen drawer so she could scribble out and change letters, I love hate your Eric guts.

“We don’t say ‘hate,’” you told Bailey.

“We do hate Eric, Dad,” Andie said before taking the Sharpie, then turning her gaze onto me. “But don’t teach my kid to deface property that isn’t hers.”

I was confused but I wanted Andie to like me. You told me not to worry about her, but all I did and all I do is worry about her, worry when her mother died, worry when she and her friend Raquelle were both in the backseat of that police car. When Bailey moved in with us at 15, Andie did the same then, left voicemails claiming we’d stolen her daughter. But Andie never asked for Bailey back, and Bailey knows this.

A play about a daughter being wanted until she isn’t. A play about you being here until you aren’t. A play about her latest note, left early this morning, before I was awake:

A dog named kimchi instead

Andie

One night later, my father died. A cruel joke! A dramatic irony! An Act III twist!

Roll back the tape. The day after my botched premiere, I left Rocky’s house in the early afternoon, going back to mine only long enough to microwave an old pot of coffee, when I heard a knock at the door. It was Pete, smelling of Rocky and ground beef. He said, “Someone at the bar gave me tickets, if you want to go.”

Good Toys was sold out, but Pete had been given two orchestra seats for the Second Night of its Highly Anticipated Premiere. He held them out, fanned, on display.

“With you?” I asked.

“I figured it would be you and Rocky,” he said.

And I remembered how long it had been since I had been anywhere with an agreeable man, and I let myself be mad again that Rocky had forgotten to attend my play, and so I tipped my toe into the edge of a question—“Well, you said you do like plays”—and he agreed as expected—“I’d love to see it with you”—and we went together.

In the theater, we got plastic cups filled to the brim with red wine. I went to turn off my phone because I respect the dignity of art only to realize my phone had already been turned off, and had remained off, since the night of my own premiere. I found a black screen and said, “Oops.”

The house lights went down and the curtains pulled apart. A minimalist set, a living room. Sienna’s play seemed to be about a dinner party and a little girl and a little boy and a rotisserie chicken and a loose dog. They used a real dog, a trained one.

The next morning, I woke up with Pete in my bed, one of his hands cupped over my soft midsection. A plastic wine cup rested on my sternum. Outside of the play, I recalled almost nothing about my night with Pete, except for how agreeable he was to the whole thing. It all just felt like the necessary conventions—wine, sit, fuck, the things you do when you see play.

Then a knock at the door, and it was Rocky. I told Pete to hide and I opened the door.

“Andie,” she said, like she was out of breath. Crying, I think. “Andie, baby. Your dad.”

They had all been trying to reach me, Sienna-Bodie-the hospital-Bodie-Sienna-the hospital-Bodie-Sienna-Sienna-Rocky-Rocky-Rocky, to tell me to come, that it would only be a matter of hours. But my phone was dead. My phone was dead because of the play because of Pete because of Rocky. They had been trying to reach me. I was at Rocky’s house because of Sienna’s play because of my play because of Sienna, they had been trying to reach me. I am angry, suddenly, at Rocky for bringing Pete into our lives. I am angry, suddenly, at how agreeable Pete is. I am angry, suddenly, at Sienna premiering her play the same night as mine, to keep me distracted, to keep me unavailable while my father died. It rushes through me, this rage, this belief that they have all caused my father’s death. I am having trouble finding the themes, I am having trouble tracing the causality.

I muted myself to Rocky and I made Pete get out. Rocky saw Pete leave, out the door and down the apartment staircase in his dirty underwear. I muted myself to her rage. “This town’s not big enough for the both of us,” I said. I locked my door. My bed still smelled like Pete and ground beef. Maybe Pete and ground beef saved my life because I would have crawled back into bed, and who knows, really, if this time I would have re-emerged. So, instead, I lay flat on the tile of my kitchen, trying to recite my play in its entirety.

Sienna

Good Toys is set in an ambiguous present day and is about a family of children making sense together of an unspeakable tragedy. That was, at least, what the marketing team sent me. “Let audiences do their own imagining,” they urged when I questioned their rewrites, their lack of specificity. But what are we, if not all of the things we never were? This is a play about you, and us, and your daughter who loved you, and her daughter who loved you, and the wife you left behind. Good Toys is a play about all of us in ruin, and the tragedy is a family torn asunder by the greed of hateful isolation.

Andie

In the following days, I am struck by a number of compulsions. I take notes as they come to me, edits on Sienna’s play, feedback on lines or what the characters should have been named, and I write them down on sticky notes. I leave them at the house, anonymously. Maybe they will help. Maybe they won’t. I think she’s on to something, sort of, a bit, almost, a not-quite-there brush with actuality or punctuality or musicality, but something is askew, and I am compelled to help.

Of the texts and calls Bodie and Sienna have sent me, there is one that interests me:

Funeral

The funeral is set to premiere on Thursday afternoon, a matinee, in the famous downtown chapel with a magic staircase that does not contain a single nail. I am compelled, once more, and I decide I must attend. Everyone is already seated when I arrive, but there are no plastic cups of wine. I spy Sienna in the front row, wearing all black. I spy Bodie beside her, wearing all black. I spy that guy beside her, wearing all black.

I find my way to the front of the room, my lines memorized, wearing blood-red burgundy that was one my mother’s. I am aware of what I have become, just a few pocket stones away from the Lonely Cunt they put into stories like these, chain smoking, with cat litter in her hair, using a diaper to mop her brow. I am here to play this part beautifully, and luckily for Sienna, I need very little direction.

“My dad and I,” I say, “remained friends until the end.”

The casket is open. This part is played beautifully, too. No movement, not even the slightest subtleties of breath. One thing you can say about Sienna, especially when I consider the live dog from Good Toys, is that set design is immaculate. Perhaps critics would use the word “flawless” when they describe the corpse.

“Dad,” I say, with a tear in my eye, knowing this is my showstopper, my “American Pie,” my Lucky’s Monologue from Godot. “You dreamed of being a good person. You dreamed I would be one, too. I believe this made you happy until the end, that you believed goodness was enough. You were a good man made better by my mother, who was a good woman. I hope you can rest now. I hope you are satisfied and full. I am certain I will miss you terribly.”

Only with the final stroke of the final word do I recognize that I have recited the boy’s monologue from Good Toys. Sienna is watching me, frozen.

I race out of the chapel because I do not want to stay for The End of the show. When I open my car door to get back inside, I feel a hand on my shoulder, and I turn. Sienna stares back at me, her eyes glossy. She has a mole above her left lip, and I have never noticed it because I was always noticing my father. Without him around, I notice her suddenly, in her totality, and when you notice her long enough, you notice she is the kind of beautiful that makes you sick with comfort and envy.

“That was very touching,” Sienna says to me.

“A little derivative,” I reply, starting to get into my car.

“Before you go …” She stops me, puts that hand back on my shoulder. “Bailey and I, we are getting brunch tomorrow. At the Meadow. That was your favorite spot, right? I remember you liked the corned beef hash?”

“I can’t tomorrow,” I say.

She looks down, then back up at me, with a kind of smile she always uses that I will never understand. Almost defenseless, like she is not afraid of it being taken from her. “Please. One hour.”

“I’m editing a play tomorrow.”

“One hour of your life,” she goes on. “I think your father would like us all to be together.”

It was a good line, I have to give her that. Convincing.

Sienna

She memorized it. Do you think it was a compliment?

One day, we will share in this pain, I hope. We could have been friends. You always noted our similarities. Both of us, writers. Both of us, only children. Both of us, allergic to dairy and ragweed. Both of us, daughters of mothers who died.

Andie

The next morning, I find myself at the Meadow, for what has been longer than one hour of my life. Sienna and Bodie are talking about sharing bank accounts with men and I can’t believe this is what they invited me to, that this is the brunch I needed to attend. Did I need to bear witness to Bodie’s final stages of social decay? We have fought for so long as a female species to open our own bank accounts, all ours all alone, and now Bodie is proud that she is sharing one with some shapeless man?

“His name is Michael,” Bodie snaps back at me, as if I said it all out loud. Honestly, I cannot keep track, anymore, what I say out loud and what I say out quiet.

“And we’ve actually learned a lot about partnership from Sienna,” Bodie adds.

“Like submitting to a husband?” I say. “That’s how they do it in her culture.”

“Mom, that’s racist,” Bodie says, throwing her napkin onto the table.

“Andie,” Sienna says softly.

“You are the problem,” Bodie tells me. “You are the person everyone worries about at funerals and baby showers and weddings and normal things that bring normal people together. You are always the problem. Do you know how hard it is to have to know you? We want to stop knowing you.”

“No, Bailey,” Sienna says.

“Did Sienna write that?” I ask her. I’m laughing, which doesn’t feel right, but it’s the only thing I can do, it’s like my body is convulsing with shudders of uncontainable guffaws.

“It’s like you have no original thoughts,” Bodie goes on. “And that’s fine, right? Because all you create are word-for-word replications of better writers.”

The grit of Bodie’s voice was always like lead shavings to my ears.

“Bailey,” Sienna says, lowering her voice to a barely-there sound.

“No,” Bodie tells Sienna. “It’s not fair. She read one book in college and decided that meant she was more interesting than all of us. We don’t need to be condescended to because she thinks we’re idiots for being nice to her. No one wanted her at the funeral. Grandpa had no idea what she had become, he would not have wanted us to have anything to do with her.”

“That’s a lot of plural pronouns, Bodie,” I tell her.

Bodie cannot think of herself from inside, always outside. I think this will be her downfall, the thing that eats her alive like her will was never free to begin with.

“You can leave, Andrea,” Bodie shoots back.

“Why was I invited, anyway? What did you want from me?” I ask them both.

“Maybe I just wanted you to notice me like a normal person,” Bodie screams, and everyone in the restaurant looks over. “Imagine that.”

Sienna

I was asking her for the simplest thing, to just be here with me. I am afraid your Andie cannot tell what is real from what is not, anymore.

Andie

Who are you talking to?

Sienna

“Who are you talking to?” Andie asks.

I stare at Andie as she stares at me.

“What did you say?” I ask her.

I could swear I heard her speak. You always said she used to do this, pretend she could read your mind, catch you off guard, make you wonder if she actually could. She does have that way about her, that godlike air of impossibility. This sweet brunch, with Andie’s beautiful daughter, the two of them, in my eyes, reflecting pools of each other.

Andie

Listen to you. I wake. I cry. I decay. I pine. I spit. I ferment. Listen to you, with your sweet narration. Your Memoirs of a Geisha-ass narration. Little meek mail-order bride, little meek paper wife.

Bodie

Mom—

Sienna

This isn’t about me. Please. This isn’t about me.

Andie

EVERYTHING IS ABOUT YOU!

(SIENNA, ANDIE, and BAILEY are moved from inside the restaurant to the beautiful garden patio. Twinkle lights, ivy, fountain. WAITERS stand by watching helplessly.)

Andie

This is it, this is your play, this is a play about hags and rats and beef and YOU. You wrote it, you made this, now we are stuck inside it, in this spiral of YOUR FAULT.

Sienna

I don’t care about the fucking play!

(ANDIE and BAILEY do a double-take.)

Sienna

What you don’t want to know is—

(ANDIE tries to light a cigarette, a WAITER stops her.)

Sienna

—what you don’t want to think about is that you missed his final years because you hated me so much and I’m afraid you’ll never forgive yourself.

Andie

So this is, what, atonement? Covering your bases?

Sienna

You don’t have to be my enemy.

Andie

Ask me about my mother. Have you ever?

Sienna

I ask you about your mother almost every time we are together. I asked you about your mother the first day we met. You told me how you had her hair, about her horses, about how you trained them together. I have thought about you and your mother every single day since. And I also—

(ANDIE picks up a Bloody Mary off someone’s brunch table and starts chugging.)

Sienna

—I also know your mother hurt your father terribly, and I have tried, I have tried to keep space in my heart for all of it.

Andie

Bullshit.

Bodie

Grandma burnt Grandpa with a cast iron, Mom. Grandma was manipulative. Where do you think you got it from? Wake the fuck up.

Andie

That’s what Sienna wants you to think. That’s what she wants, don’t you see? You think I’m crazy, but I know things. Bodie, I know things.

(WAITERS remove the tables and chairs, preparing for the Showstopper, the Big Number, the Ensemble Finale.)

Sienna

I have never, ever lied about you, Andie.

Andie

The thing about you and me, Sienna, is I am better off to have never known you at all. But, the thing is that you need me because I’m all you have now. I know what you are, and you need this family like a little leech. You should be alone, but you won’t let go of us.

Sienna

The actual thing is that I know what you are. You always blame everything on other people so you never have to acknowledge how unbelievably, endlessly miserable you are.

(Maybe BODIE said that, actually? Who can be sure? Sometimes the harshest things can’t be bracketed. You just put them onto the page and figure out who they belong to.)

(ANDIE exits.)

(And now: SIENNA, at home, pacing.)

Sienna

I feel a chill. I wonder if it is you. It catches me by surprise, this feeling, late at night and in the dark. So much of what Andie said, so much of it correct—that without you, I have nothing. In the daylight, I pace the rooms, I talk to you, I make an altar of your favorite books. It is hard to know if anything moves, but, inexplicably, the hours do, they must, and the weeks eventually pass. I am now just a woman who opens doors to people with condolences. None of them are you, but I welcome all of it. A play about welcoming all of it. And suddenly, on a bright afternoon, your daughter is at my door. I feel a surge of hope: Will she stay? She’s knocking this time, and she doesn’t run off when I answer.

(ANDIE knocks at the door, and doesn’t run off when SIENNA answers.)

Andie

I got something for you.

(ANDIE grabs a stack of bound papers from her backpack and hands it to SIENNA with the cover facing up. “Good Women.”)

Andie

It’ll keep you safe from yourself.

(SIENNA holds the script tightly to her chest. ANDIE turns and walks off stage.)

CURTAIN