How Deep Is Your Love? – On Writing, Fangirling, and the Best of the Bee Gees

Family movie night in 2020 was often pretty bleak. Though new content was limitless, we somehow always blew through our carefully curated Watch List too quickly and found ourselves scraping the bottom of the streaming barrel. By the time the first Covid summer was over, even calling it “family movie night” was generous. Often it was just one person declaring their pick while the rest of us took a nap on the couch. It was group viewing in the loosest sense. And it was nobody’s fault. We were tired of movies every night. Tired of the pandemic. Of each other’s company. Some nights, when everyone was asleep except the one who selected the evening’s entertainment, it was almost kind of nice to watch something, for all intents and purposes, alone.

Alone is how I watched, and delighted in, The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart, Frank Marshall’s documentary, and alone is how I came to realize something about myself and my taste in literature. A pretty bold statement to make about a biography of a band whose hits are nearly all older than I am. True, I came to the film already a dyed-in-the-wool Bee Gees fan, but somehow How Can You Mend a Broken Heart still had a lot to teach me, mostly about my writing.

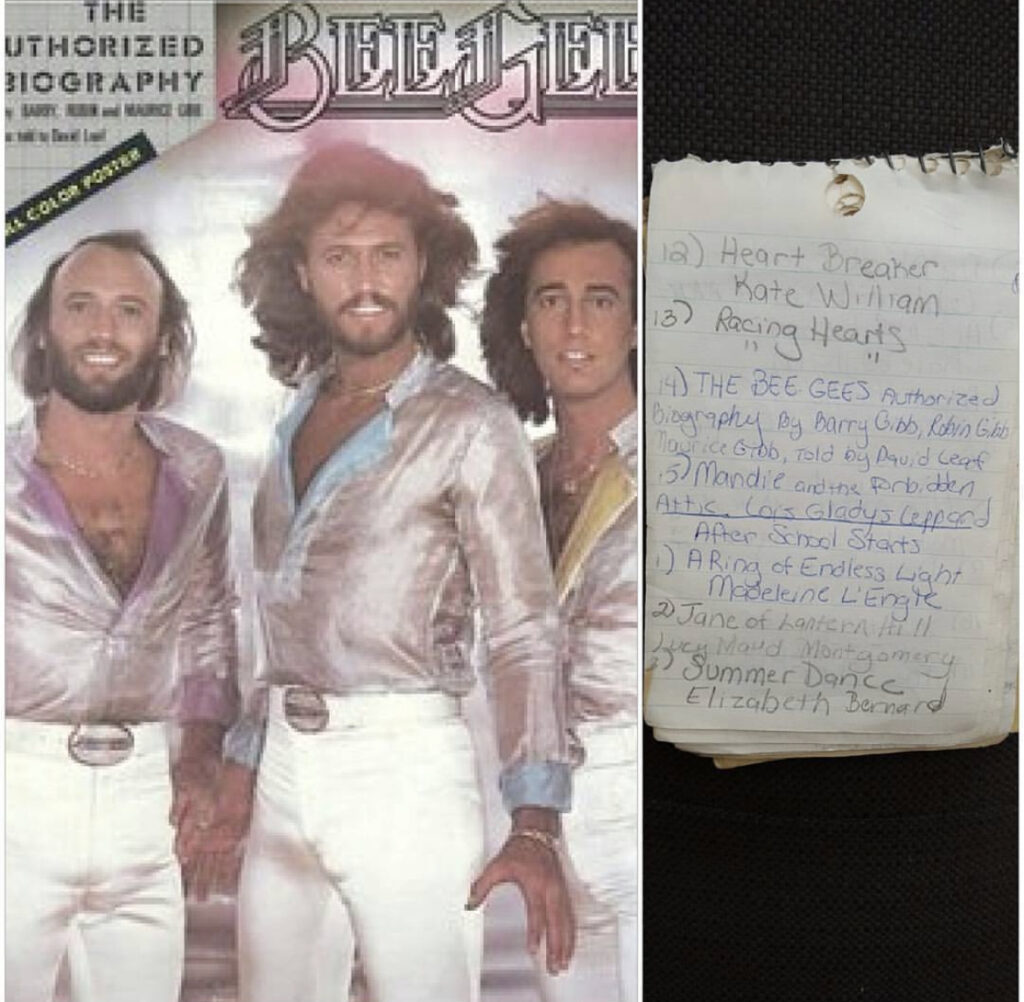

I had considered myself something of a self-proclaimed Bee Gees expert since 1988, the year I rocked scrunchies in middle school and the year I read, cover to cover, the Bee Gees: The Authorized Biography by Barry, Robin and Maurice Gibb. A few months before I tracked down and checked out that book from the library, I had stumbled upon my father’s dusty old Best of the Bee Gees album, and a rabid fan in me was born. While all my friends were screaming themselves hoarse over New Kids on the Block, I was busy trying to decide how to best insinuate myself into the Gibb family. As the doodled hearts on my book covers would attest, I had an undying love for the band, and I wasn’t hesitant to tell the world about it. Later in the fall, I’d even tag along to a babysitting gig with a friend during which I’d insist on playing my dubbed Best of cassette on the stereo after the children in our charge went to sleep. I would not be invited back.

It was weird to obsess over the Bee Gees in the 80s. Though I knew nothing about the “Disco Sucks Movement” earlier in the decade or any of the pop culture backlash against the band’s gargantuan popularity, I knew my love and admiration for them was an unpopular opinion in middle school, a place with a culture that revolves around trying not to be unpopular.

And yet. There I was, Authorized Biography (with all its copious chest hair) in hand, unable to resist scratching that Bee Gees itch. Listening to those songs over and over again because I recognized something in them which I would only later chalk up to a certain style of storytelling.

The Bee Gees were the first songwriters to ignite my interest in lyrics. I actually paid attention to the words they were singing, and as a result spent quite a bit of time pleasantly puzzling out what those words might mean. In that way, their Best of became a gateway, of sorts, turning me on to “oddness,” or what felt odd in my limited middle school experience of the world. A song that opens, out of nowhere, with a Gregorian chant? Check. A song that drops listeners into a conversation between a group of trapped miners, huddled together in the darkness? Check. A song addressed to a death row prison chaplain? Check. I had never heard anything like these songs, and I didn’t yet have the craft vocabulary to explain what it was that drew me to them. But in revisiting them during How Can You Mend a Broken Heart, by listening closely to the words again, I recognized that they were populated by unexpected characters, and made expansive by the suggestion of a narrative beyond what the verses and choruses provided. I recognized, too, that the power of suggestion and the unexpected were speaking to the budding short story writer in me.

“Listen to this one. Can you hear the words?” I remember asking my friend at that babysitting gig. The stereo in that house was so much better than the crappy boombox in my room at home, and I kept turning the volume up higher so that she could more fully appreciate the lyrics. Only, she wasn’t as captivated as I hoped she’d be. “What does this even mean?” she kept saying. Or sometimes, “I don’t get it.” Or “This is so weird.” She was right. She didn’t get it. And it was weird. Wonderfully weird. That was precisely what made the songs so exciting to me, but it was something I struggled to convey to her, and that experience of disconnect over the weirdness became one of my first memories of trying to talk about something that felt too ineffable to capture in words, too magic to methodically explain. It simply moved me, that album full of songs, of flashes of a world beyond our own, but I was alone in being moved, and it was a lonely feeling. Not being able to share. Not that it made me love those songs any less to know my friend didn’t love them too, but it did make me long to better understand the mysterious pull those songs exhibited on me.

In time, I’d recognize that pull as a desire to write myself. Not songs, but stories, which feels fitting because, though the harmonies are lovely on that album, it was really the storytelling above all else that moved me. The brevity, the oddness, the glimpses of worlds existing beyond three-minute tracks. Over the years I’ve had people admit to me that they don’t like to read short stories because they’re too inscrutable, because they don’t like having to work so hard to puzzle out what something is about. But the slippery quality of the form is exactly what I love about it, and what I learned to love back in those days I spent trying to convince my friend that if she just gave the Bee Gees one more listen, maybe the same worlds that revealed themselves to me would also reveal themselves to her. That’s not to say I became a story writer only because I was a late-to-the-party Bee Gees fan, but that my appreciation for the ineffable and the suggested were certainly influenced by the singular strangeness that album brought into my life and by the magic alchemy of the right song introduced at just the right time.

Because timing, after all, is everything in how and why something does or does not appeal. A few years before the pandemic, I found myself at a beer-pairing dinner at a nice restaurant. The food, as I remember it, was abundant, as were the generous pours. By the time I got home I could only recall one beer I had tasted over the course of the evening, a raspberry sour paired with dark chocolate. As someone who actively disliked sours and dark chocolate, on the way home I had a hard time squaring away with myself the fact that a pairing of precisely those two things had been my favorite of the night. Could it have been the surprise of finding something to appreciate in that which I had discounted? Possibly. But it also seemed like more than that. A combination of tastes lining up just so at the end of a long night, in a way I had never experienced before, in a way I would never again be able to replicate. No amount of trying out other sour and chocolate combinations over the years was quite as successful as the first one, and the fact that I couldn’t even put my finger on why it appealed to me is probably the reason I’m still thinking about it years later. It’s compelling to be compelled by what we can’t explain to others and even more so by what we can’t understand ourselves.

There’s a scene in the Bee Gees documentary where Noah Gallagher of Oasis tries to describe a certain kind of magic that occurs when siblings sing together. “You’ve got the brothers singing. And when you’ve got brothers singing it’s like an instrument that nobody else can buy. You can’t go and buy that sound in a shop. You can buy a Fender Stratocaster and put it through a VOX amp and sound like Buddy Holly. You can’t sing like the Bee Gees because when you’ve got family members singing together, it’s unique.” And what is an unreplicatable sound if not an ineffable one? And what is taste, in beer, in music, in most things in life, if not too personal, too unique to fully explain? No one is ever going to love the first band you fell in love with the exact same way as you love them. No one will ever fully understand.

Back in 2020, I may have been the tiniest bit miffed that everyone conked out during my pick for family movie night, sleeping all the way through the film that offered me such rich personal insights about how the Bee Gees helped guide my way to writing short stories, and about the exquisite fool’s errand that is trying to explain anything to anyone where the heart is concerned. In the end that’s what those revelations were: personal. Chances are I still wouldn’t be able to articulate how deep my love was for “How Deep Is Your Love?” even if my family had stayed awake on what proved to be an unexpectedly joyful night during an otherwise bleak period. “Oh, you’re a holiday,” begins the opening track on the first Bee Gees album I ever listened to. Maybe not entirely inscrutable, but also not nearly as on the nose as what my long-ago friend preferred, “You Got the Right Stuff (Girl).” But sometimes it’s best not to even try to explain these things.