Jealous, in the Best Way Field Notes on I Know About a Thousand Things: The Writings of Ann Alejandro of Uvalde, Texas

I’m jealous of a poet who never even tried to get published. No, I don’t mean Emily Dickinson, the reclusive godmother of American poetry. I’m talking about Ann Alejandro, a writer who wore a Texas Rangers ball cap when she rode her favorite mule, Chess Pie, in her beloved small town of Uvalde, Texas. After her death in 2019, two of Alejandro’s close friends and well-known writers, Marion Winik and Naomi Shihab Nye, collected and arranged Ann’s work in a slim volume published in 2024 by Texas A&M University Press. The book is called I Know About a Thousand Things: The Writings of Ann Alejandro of Uvalde, Texas.

My jealousy of Ann Alejandro is layered but not without redemption. It’s a jealousy that circles around toward celebration. I Know About a Thousand Things is an assortment of poetic musings pulled from letters Alejandro wrote throughout her adult life and arranged by topic. Winik and Nye spent decades highlighting “the best parts” of Alejandro’s letters, quietly planning to one day compile them into a book. I’m envious that, while she lived, Alejandro was able to leapfrog the stresses of trying to get published. I’m envious she had friends who saw the value in her words, who saved them and ultimately shared them with the world. And I’m envious of a woman who lived the way we all aspire to: fearlessly and with a joyful attention to the present.

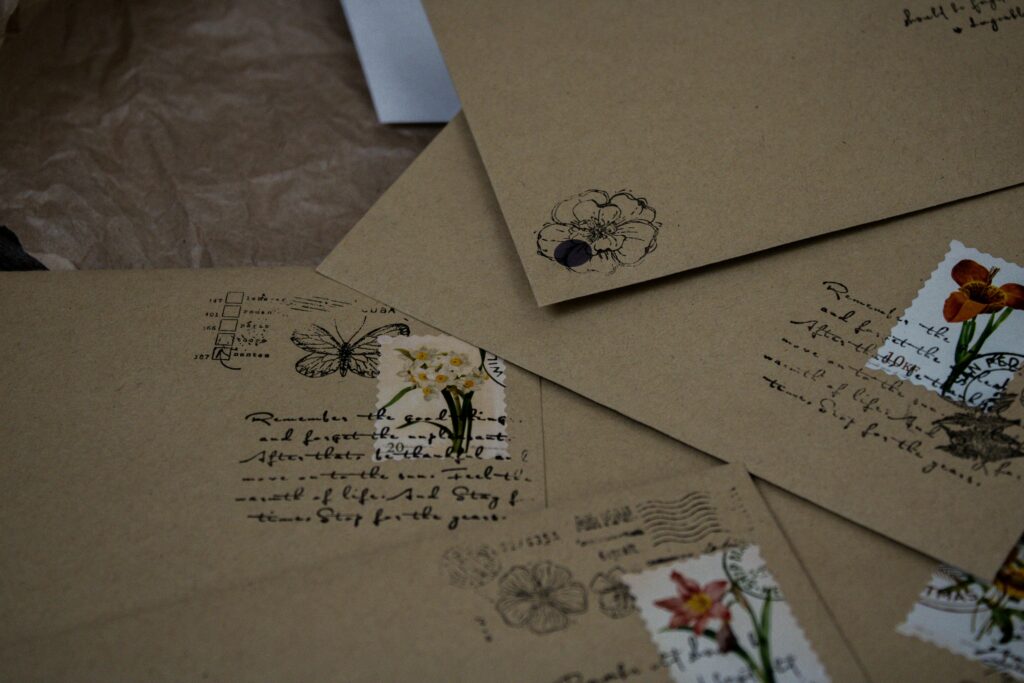

Alejandro’s mode of sharing her writings was convivial and personalized—handwritten letters to actual people in her life. As a skilled poet, she knew how to describe the specifics in ways that speak to the universal, so that reading portions of her letters does not feel voyeuristic, but like a warming bonfire on a wild ranch—invitational. Though her letters were never addressed to me, I feel their pull and charm—and their sweet irony: her personalized letters have universal appeal in a world where we share universally on internet platforms yet still feel unseen.

Not only do Alejandro’s writings invite us in, but they also read like a celebration of abundance, especially a sense of abundance about her beloved Central Texas Hill Country. I read the whole book in one sitting and came away joyfully envious of a woman who clearly loved her whereabouts. From the chapter called “Circle of Stars,” she writes:

“I want heaven to be a very un-diaphanous place where you make or think in sentences with nouns and strong short verbs and well-chosen sparse adjectives, like a cottonwood tree or the waterfall bank of a perfectly clean hard-running Nueces River, beautiful but familiar as your favorite old shoes and the smell of too-hot cedar trees, and the smell of sweet earthy whitebrush in a hollow just cooling off at sunset with the warm air wafting above it, pressing that basil-lily dusty uncomplicated odor all the way down your throat and mixing with the smell of your horse or mule’s sweat and how Lee always smelled like a clothesline full of cottons just as the heat had broken.” (p. 18)

Alejandro’s writing has an abundant, listing quality. But the book also reveals a life of deep physical pain. Ann suffered from a debilitating, mysterious illness that she wrote about often to friends. She writes, “I know a thousand things about pain, maybe twelve thousand.” (p. 53) I wondered how illness factored into Ann’s ambitions as a writer. Perhaps illness is why Nye writes in the book’s foreword, “Ann Alejandro is the best writer in Texas that almost no one has ever heard of.”

In February 2025, I chatted with the book’s editors, Naomi Shihab Nye and Marion Winik. Nye reflected, “Ann really didn’t talk about publishing much. I mean, every time I had a new book come out, she would order it, come to town for the book party. And I could tell there was a yearning in her. I always felt like saying, ‘Ann, you’re a much better writer than I am. This should be your book.’ I wanted to encourage her to send her stuff out. But she had a little defensive shield against it. ‘I just can’t do that.’ I felt like maybe her physicality, her energy, was always in jeopardy all those years—that getting any rejection would have been too much for her.”

Winik went on to say, “It’s too much for most people. I mean, the path to be a published writer is a very hard one most of the time. Ann had the sense of what would be involved in sending things out. She was more into writing letters than she was in scaling these unfriendly walls of the publishing establishment. Ann sensed that she might as well get on with the work of her own life.”

Whether it was from illness or a sense of her own limitations, Alejandro didn’t pursue many publishing opportunities. She published a small chapbook in 1995 and had one poem published in an anthology of Texas poets, called Is This Heaven or What? Nye says that Ann’s poem in the anthology was the most celebrated one. But beyond those public offerings, Ann saved her writing for letters to friends. She was a mother of two boys, a creative writing teacher, and an animal lover with a whole ranch to maintain. She was busy. At some point, she quietly pivoted from pursuing publication to being present in her very full life.

The majority of creative writers are jostling and jockeying to be known. We’re plagued by a desire to share our insights and stories with the world. No writer wants to die unknown. But plenty have. As a writer in my fourth decade of life, the alluring subtext of Ann’s story is a kind of permission to tap out of the publishing race—to give up on a system that most of the time only rewards the dogged. My life is full, just like Ann’s. I’m a mother, teacher, and writer. And most of the time, I’m really tired. Alejandro’s story whispers: Drop one’s own pressure (like heavy feed sacks, Ann might say) to be a popular writer with steep publishing credits. Knowing that Alejandro’s poetic ramblings were scattered in letters lets me imagine, for a moment, a different approach to a writing life: live abundantly; write abundantly; offer your writings in abundance to friends and family.

Ann Alejandro was not only a teacher, mother, writer, and proud Texan. She was also a woman with writer friends. By the end of the book, I didn’t need for Alejandro’s poetic insights to be famous. They would have been just as vivid if she had written them to me personally and stuffed them in an envelope. But an enviable layer is added to the top of her story—that her writer friends saw her potential and planned to publish her work posthumously.

On June 7, 2019, Ann died at her home in Uvalde that she loved so much. She was 64 years old. Shortly before she passed away, she humorously said to Winik and Nye, “Make me famous.” I’m envious of Ann’s friendships—people who weren’t willing for her writings to die too. Friends that went the distance to make sure they kept a promise to a friend. After all, what did Nye and Winik have to gain from publishing their friend’s letters? Not attention to their own work. Not book sales. What they gained by bringing I Know About a Thousand Things into the world is the same thing we gain as readers: more of their friend, distilled to her essence.

Lastly, there’s something lucky about not having to witness more pain in the world. To leave this planet with a happy view of a place you loved could be called a blessing. That is certainly the case for Alejandro, who would never live to see the day when unthinkable gun violence ripped through her beloved Uvalde community on May 24, 2022. Winik speaks to this in the afterword, saying:

“As the news came in [of the Uvalde shooting], even before we knew that Ann’s great-niece Layla Salazar was among the lost, it crossed both our minds that it was a blessing Ann didn’t live to see this. How could she have borne it?” (p. 87)

Ann’s absence from the horrors of that tragic day in Uvalde speaks to a quiet mercy.

I Know About a Thousand Things elicits a kind of envy—but one that stirs me. So I say, praise for Ann Alejandro’s choices in life—for the pivot—from searching for publishing notoriety to searching for a stamp and an envelope. Praise for a writer who didn’t “throw her hat into the ring,” but who wisely kept it on her head. After all, you need a good hat when you’re riding your favorite mule through the untamed Texas Hill Country.