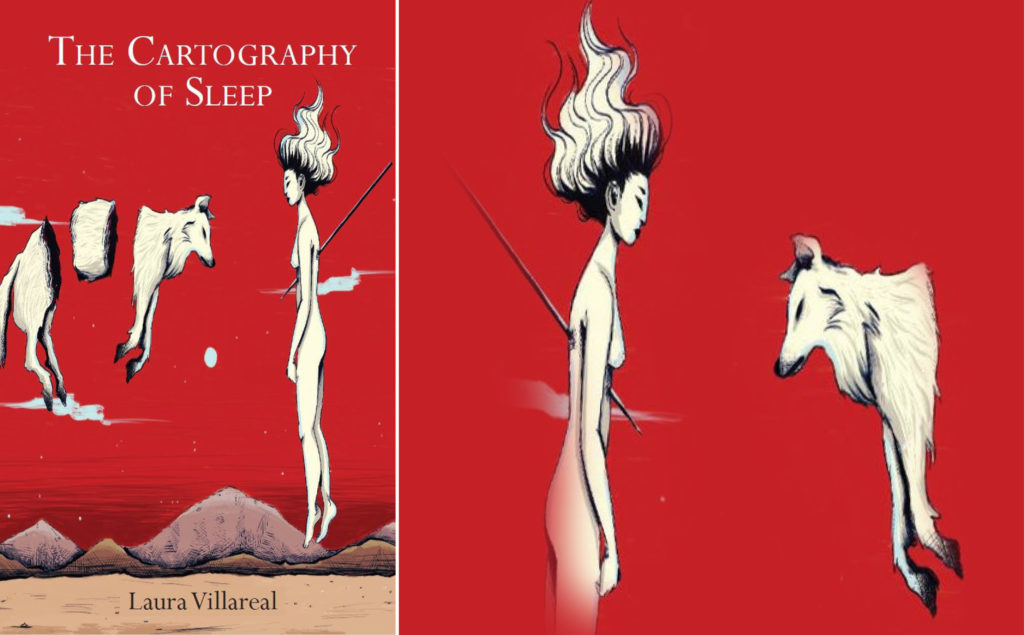

“Navigating an Inward World”: On Laura Villareal’s “The Cartography of Sleep”

Laura Villareal’s The Cartography of Sleep (Nostrovia! Press, 2018) is a visionary, cerebral chapbook. It is sometimes difficult to penetrate, but once you make your way through the surreal layers, it is well worth your time. Villareal is a master of making the strange seem beautiful with rich language and a hypnotic style. In the opening lines of the lead poem, we are introduced to the speaker’s radical vision and precise memory: “I haven’t seen the stars since August, / but I remember each pinhole of light.” We know this is a sensitive speaker, one with a near-photographic memory or at least a vivid imagination. Later, we find out more about the speaker’s interest in the astral and its relation to her lovers:

I haven’t seen the stars since August,

but seldom think of running with coyotesor chasing the full moon until it’s new again.

Except when I chart constellationson the body of a man or woman,

the restlessness becomes unbearable.

But I like it that way.

The ethereal speaker finds amusement in her connections with her lovers or friends. It isn’t necessarily always a flowery connection—“the restlessness becomes unbearable”—but the contact or friction is definitively better than simple solitude: “I like it that way.” At the end of the poem, the speaker’s predicament with her lovers is further explored:

When I disappear, I only leave teeth

marks. I can hear whimpers

& howls in the distance.I like it that way.

This speaker wants you to remember her. Even though she speaks about the stars, she still wants to feel real human touch, to feel special in her lover’s eyes. Although her relationships aren’t always smooth, leaving someone with “whimpers / & howls” is better than leaving someone in silence, unmoved: it is proof of passion and existence.

Later, in “The Long Trajectory of Grief,” the speaker announces an unspecified shame: “I wonder / if the constellations above me can lift shame or if they’re only / a temporary solution for what I feel.” The speaker is filled with shame, but from what? Is it related to identity, sexuality, something else? Next, she finds “three wild boars in the street, dead.” She sees her own isolated sorrow in the dead wild boars in the street: “Is the nature of a crash to always leave something behind?” The speaker’s relationships are like an ugly accident in the street—they always “leave something behind.” What is left behind is the speaker’s ragged heart. Importantly, though, the speaker would rather save face and not have anyone see her grief: “But I pray the vulture pick me / clean like a Tibetan sky / burial before anyone smells grief on me.” Introspective and looking to the stars, the speaker still does not want others to know of her vulnerability; she has been taken advantage of in the past, as is evidenced by her philosophy on crashes, i.e. interaction.

The chapbook is not just up in the clouds, though. There are also visceral moments where the speaker recalls domestic abuse. In the poem, “I Still Check for Monsters Before I Go to Bed,” the speaker recounts said trauma:

I want to know that you’re unhappy, that you’re 2,000 miles away,

& you can’t touch me. In my dreams,

you appear disguised as

a shoebox on my doorstep.

When I open you

there’s shotgun & flare

gun shells.

The speaker’s abuser has even intruded on her dreams. She can’t escape the pervasive harm that has been done. Ultimately, though, the speaker goes on to explain her desire to reclaim her dreams and destiny:

I’ll wake myself up

just enough to control my dream—

to turn myself into glass

before you hit me. This time,

it’ll be your blood instead of mine

Empowered, the speaker wrestles with the ghost of her trauma and promises to crush any potential future attacker. The speaker defiantly warns any potential monster “it’ll be your blood” next time.

Toward the end of the collection, we find a poem that is relatively down to earth and amusing. In this poem, “If I Invited You to Love Me,” the speaker announces what it would be like if she opened up to someone. She proceeds to make some confessions:

I’d tell you my Netflix queue is trash

because some nights elongate & I trick myself

into thinking a romcom will bore me to sleep,

but I watch the whole damn movie

until, crying, I fall asleep.

Every. Single. Time.

The speaker wants to pretend she is too cool or smart or hip for a simple romcom (don’t we all) but can’t help but cry at the clichéd sentimentality. Later, the speaker elaborates on her self-imposed isolation:

I’d tell you I’ve gone to museums 52 times

this year, but I only go when I’m lonely.I’d tell you I’m not always sure

being alone is worse than

allowing someone to splinter me.

The speaker uses an appreciation of art as a way to mask her loneliness. Avoiding loneliness is one thing, but the speaker also wonders if solitude is better than “allowing someone to splinter me.”

The Cartography of Sleep is not an easy read. It is a bit of a mixed bag in terms of the aesthetics at play. It’s beautiful and complex, but will require a couple of reads. We are navigating an inward world full of stars and dreams—the visions of a unique writer. There are references to Greek and Aztec mythology. Google them. This chapbook does, however, enrich your palate: you feel as if you’ve eaten at an artsy yet refined restaurant. You’ll want more and more, but ultimately settle for an artisan beer and a cigarette on the moonlit porch. Maybe you’ll finally see the stars again. It will be August. Pinhole of light.